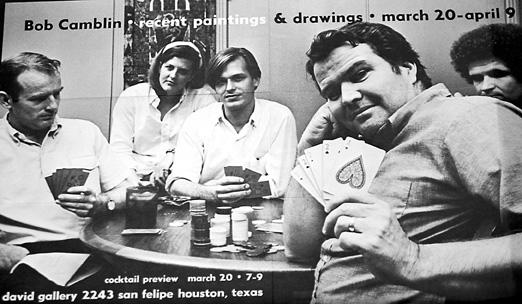

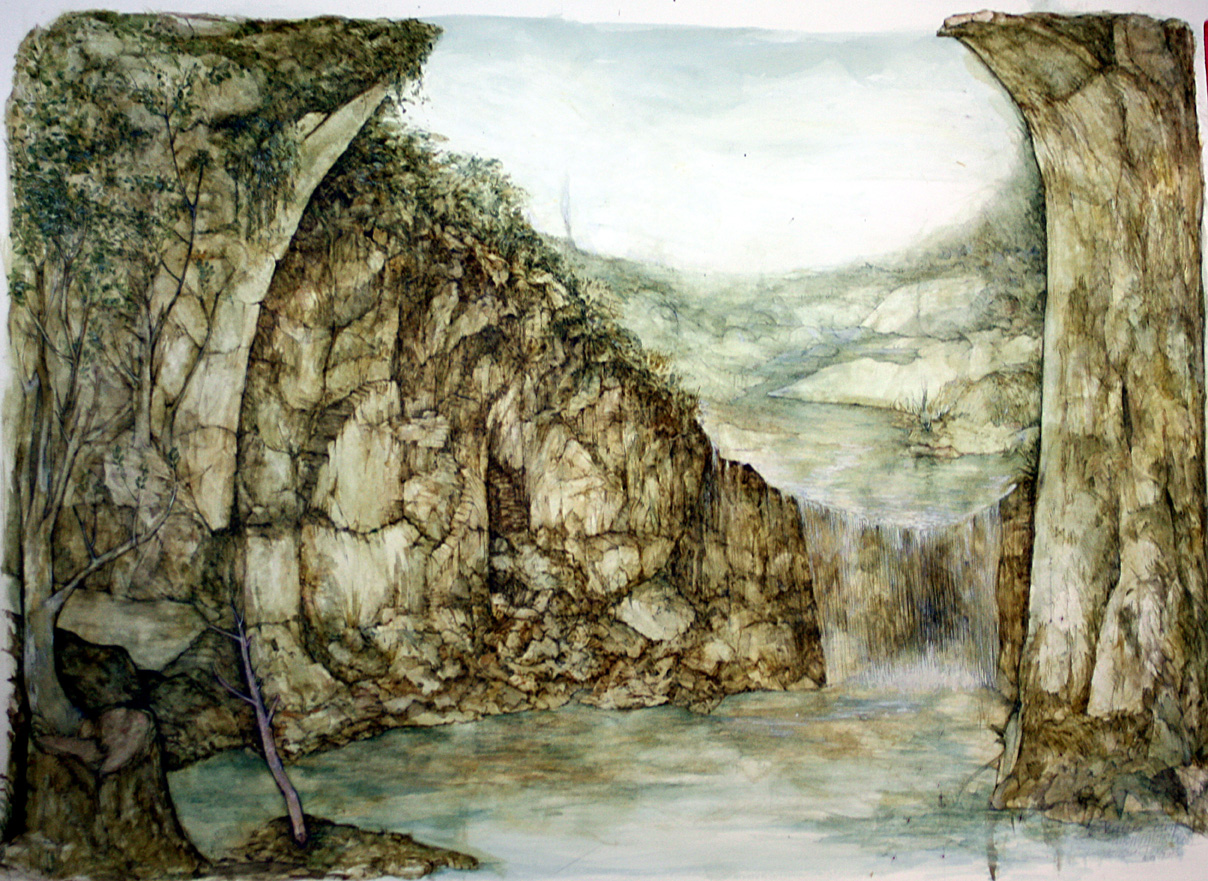

The 1970s found Camblin on even higher ground – in the prosperous and art savvy Houston. Here he discovered something remarkable – how to take art’s subjective, symbolic, and decorative functions and turn them into modern mysticism. Over the next decade, he put this philosophy to work, averaging over five exhibitions per year, from one-man and group shows, to gallery openings and museum exhibitions. In the summer of 1969 he and newly-acquainted Rice University colleague and painter Earl Staley set up studios next door to each other and set in motion a pattern of working together that yielded rich results over the next four years.

“Collaboration is a natural extension of Camblin’s artistic/human beliefs,” says Patricia C. Johnson of the Houston Chronicle, “His art tells of his physical world and his friends as much as his experiences, past or present. Camblin soon became involved with activities at the Moody Gallery and when William T. Wiley came to visit, he brought the concept of collaboration as a method of increasing opportunities for chance occurrences to open up new directions in one’s art.

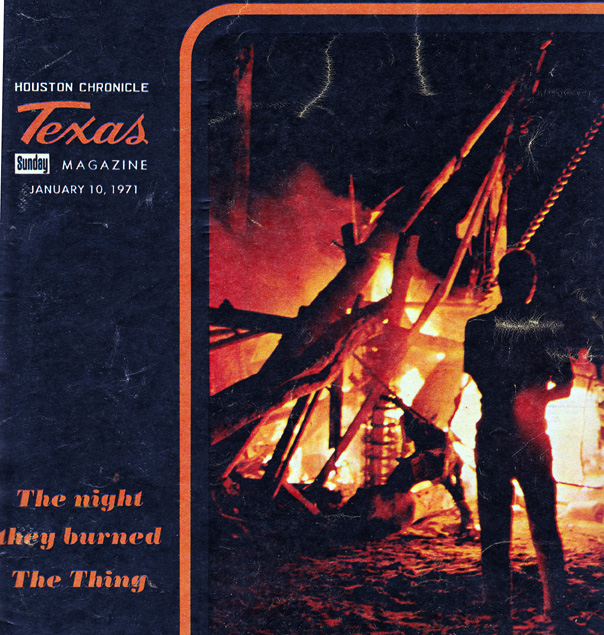

He and Staley began planning ‘events’: outings to the beach where groups of artists destroyed huge junk sculptures (1969, 1971, 1972); a tattoo show (1970) and document show (1971) at David Gallery; three exhibitions at the University of St. Thomas; countless collaborative drawings; and a three-story sculpture outside their studio entitled, ‘An Imaginary Scaffolding for the Renovation of the Statue of Liberty, to be Completed by the Bicentennial in 1776.’ The focus of these activities was on the process itself, and this point was central to their activity. The object was viewed as merely the by-product that engaged in artistic activity. In this regard, they resemble their Dada forefathers and the more anti-materialistic movements of the 1960s.”

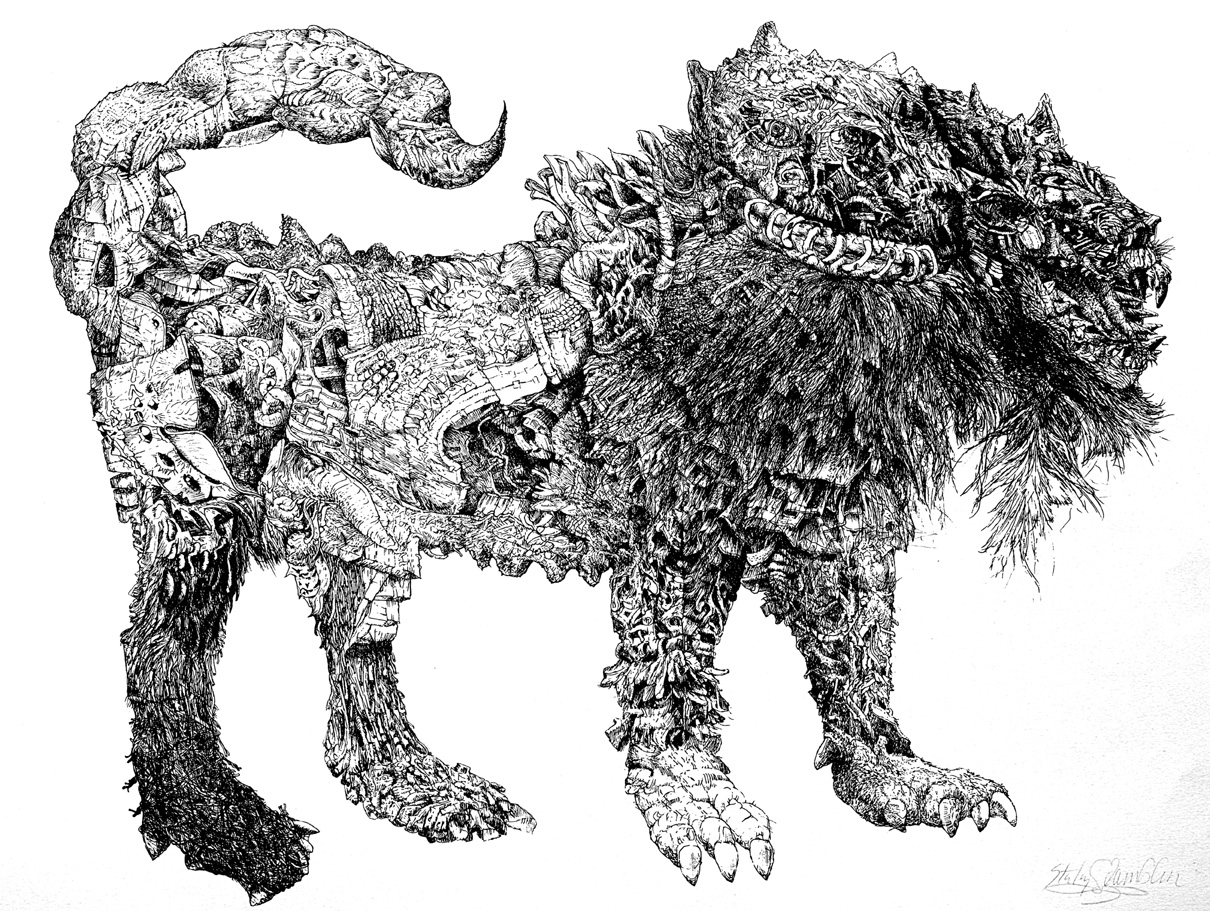

Camblin liked the power of crude and primitive work and discovered a borderline in which it didn’t look superficial, artificial, or on the other hand, unresolved. He felt closer to his large eight-foot drawings than ever before, but the style of drawing never allowed nuances of the content to develop, as he had always wanted. The new drawings were so meticulous in detail that to jazz them up would destroy the whole. He seemed to be damned if he did and damned if he didn’t.

He had the feeling that heavily relying on techniques was an easy way out and questioned the efficacy of them in general. Thinking about his students, he wondered if he should even try to teach beyond technique. He thought that through art you could find yourself and discover that every problem has built into it a value structure that leads to the optimal solution. He would say:

“Pursued correctly, a two-dimensional solution results but perhaps more philosophical attitudes have become critical to its solution. No games, yet a serious game. Puzzles that demand concentration. I wrestled with teaching only what could be taught and let the few survivors discover the truth. And the harsh truth was this: that as soon as they arrive at a technique that allowed them to do the concepts that interest them, they will soon become aware that our disposable culture requires a new novelty or they stop looking.”

“Stay anonymous and you are free from those petty demands,” he would say to the perplexed faces pursuing fame and fortune first. His message was invisible to them, and many became annoyed even as they became aware of how he was trying to seduce them into freedom. He realized art students travel the same path and yet he still struggled to get through to them:

Just because you can see the path doesn’t mean it will be easy, but it helps to know how to read the signs. The path of least resistance just makes up part of it. There is always resistance. The simplest solution is always the best. Reduce everything by two until there is one. A child would have seen the truth in not using two words when one would do.

Yet, he was troubled by the irony, if not the paradox, of instructing art to the best and brightest, who were, it seemed, incapable of letting go through personal expression.

The time came, in 1974, when he threw his hands up in despair, quit and walked away never to teach again. Free at last, he spoke of immersing himself completely in his vision of art:

“To know how good it is, you have to stop it and do something else. And when that becomes good, you have to do something else. Eventually you’ll find that there’s no separation and you, ‘eat when you’re hungry and sleep when you’re tired.’ And that is all there is. The monks say that we’re always the Buddha, but we keep forgetting it most of the time. I knew that, but now I know it! I didn’t learn anything new, but I know a lot more now.”

He once remarked that teaching people how to draw is like rocks and wood teaching about being human. He felt like he was “Living in the middle and looking to the close and far.” He spoke of:

“Becoming the battleground because at either extreme one must eventually cross the middle ground; someone must stand there and get their views from the front and rear, why not me? One must also react because the middle is constantly shifting and cause becomes cliché, left becomes right, and the man who looks too closely splits into two.”

He felt that since drawing was so introspective it was a humble path toward awareness:

“None of the glamour of film, computer graphics, large scale works, etc., demand at first glance the skills that we are incapable of. Style, art, aesthetics, culture, and history become childlike and then grow. For psychiatry to succeed it must hope that it will become unnecessary. To succeed we will have to all become artists.

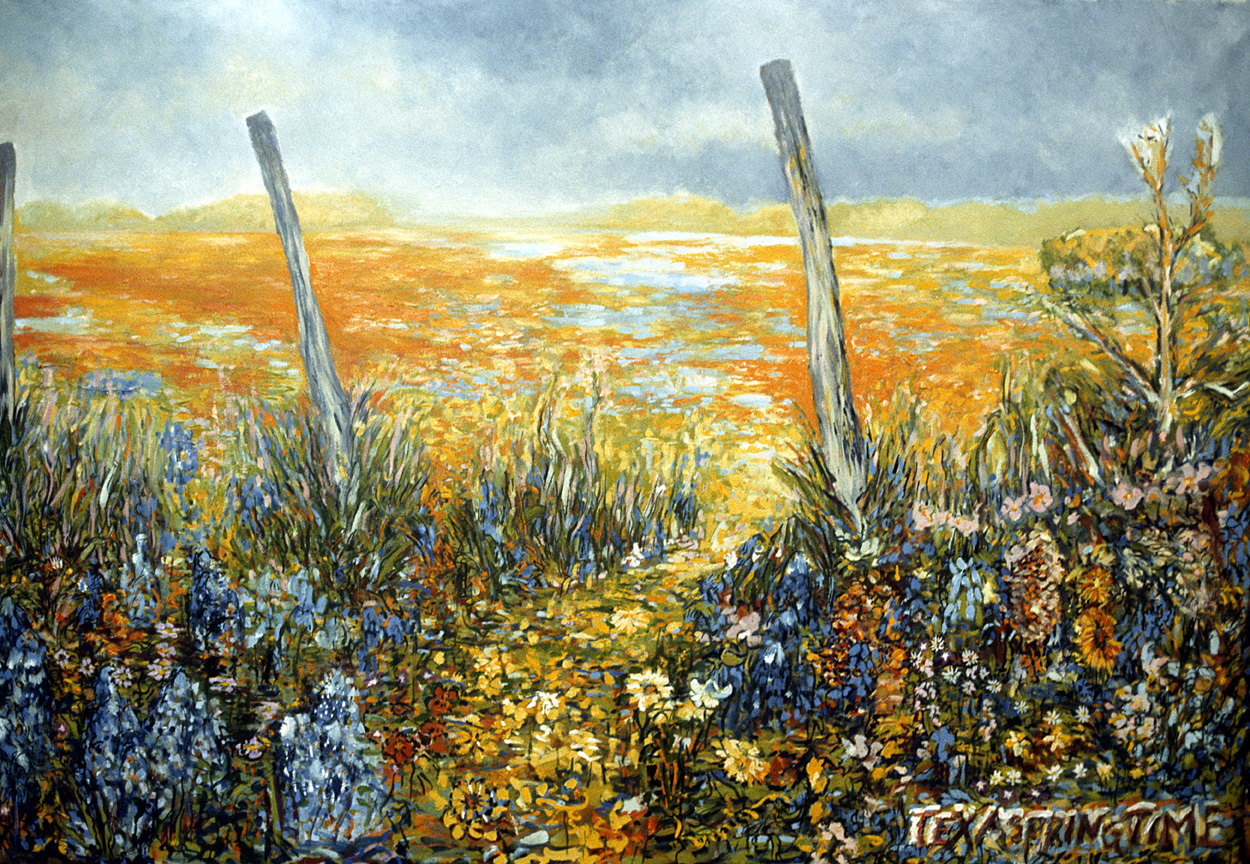

“Finding the balance was not always easy for him. He understood offsetting negative events in life and in painting with positive ones and living in the present by appreciating who he was in the moment. His five senses were stimulated constantly like most of us, but the sensuousness of the world to an artist can diminish the direction that an artist might want to follow. His limitation is that he enjoyed sight but there are four or more senses that were left out when he drew. He believed to find balance in life one must to use all six senses. Since he was stuck with eyes being his best shot, he could only get glimpses of the majesty of music, much more so with words, his sense of taste was just average, and smell was a zero. Touch is a gas, but society gets a little uptight when you get carried away feeling things.”

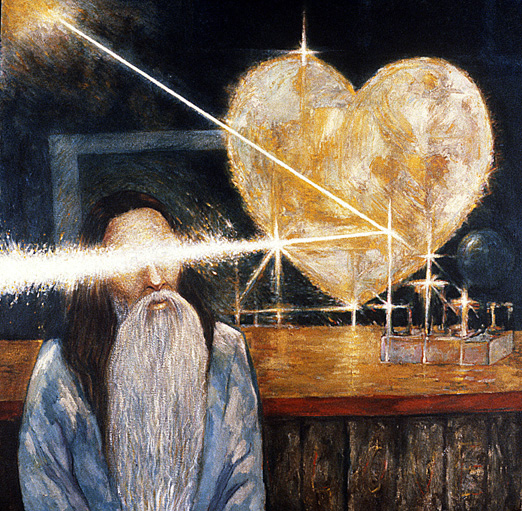

He believed art is more likely to be made when the individual ego is submerged. Without the interference of the ego, he felt that artists could make themselves available to creative possibilities by remaining open to new ideas and discovering new ways of seeing things:

“Why resist it if it doesn’t exist? If you can’t benefit, why persist? Why does the will resist so strongly the learning of its powers? Why do we have to trick the will into seeing the track? Yet, too much energy would be expanded if everything were pursued. A harmony is achieved when we will ourselves to excel and we balance in other areas and begin to say, ‘I can’t’ when we really mean ‘I don’t care to.’ When a person focuses on excelling in intellectual activities, intuitive balance diminishes. Balance is precious when evolution, change, and moving become a normal activity in the late 20th century.”

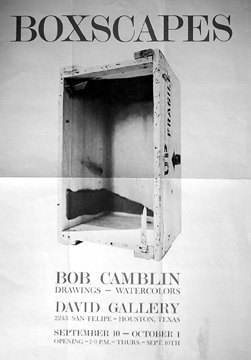

These beliefs originated with his interest in Zen Buddhism and they prompted him to eventually take the extreme step of withdrawing his signature from most of his artwork. In the mid-70s he began signing his work “anonymous box company” or “ABC” which (for people in the know) stood for “Another Bob Camblin.” By 1976 he shed all vestiges of “the individual you knew as Camblin” because he hated that he had become more important than the artwork itself.

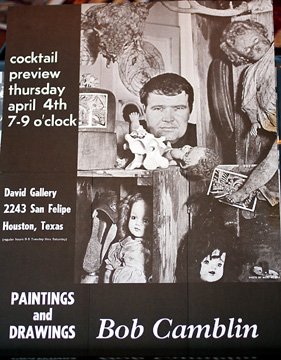

The following artwork is available in the gallery: