Back in America, faced with his reality of starving artist, he secured his first job as a mapmaker for Trans World Airlines. Within a year he quit TWA and began teaching art at museums and major universities. At each stop along the way, his work appeared in private galleries, in important expositions and was collected by high profile museums.

From 1958 to 1967 Camblin could have been found teaching at The Ringling School of Art, The University of Illinois, The University of Detroit, and The University of Utah.

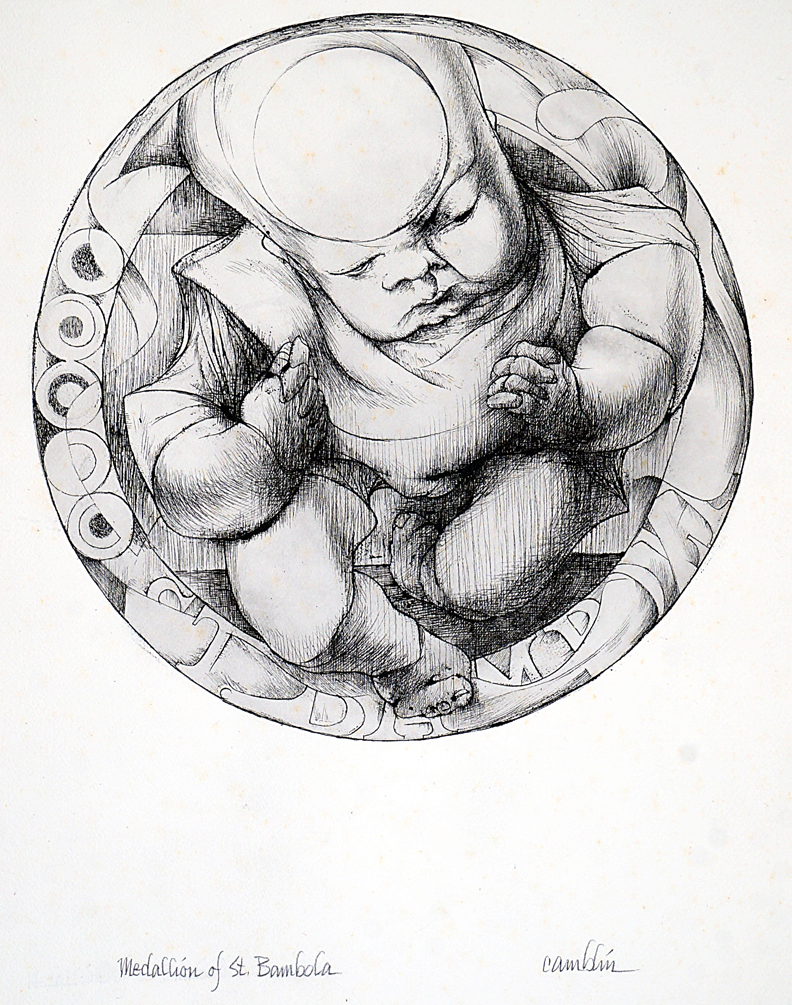

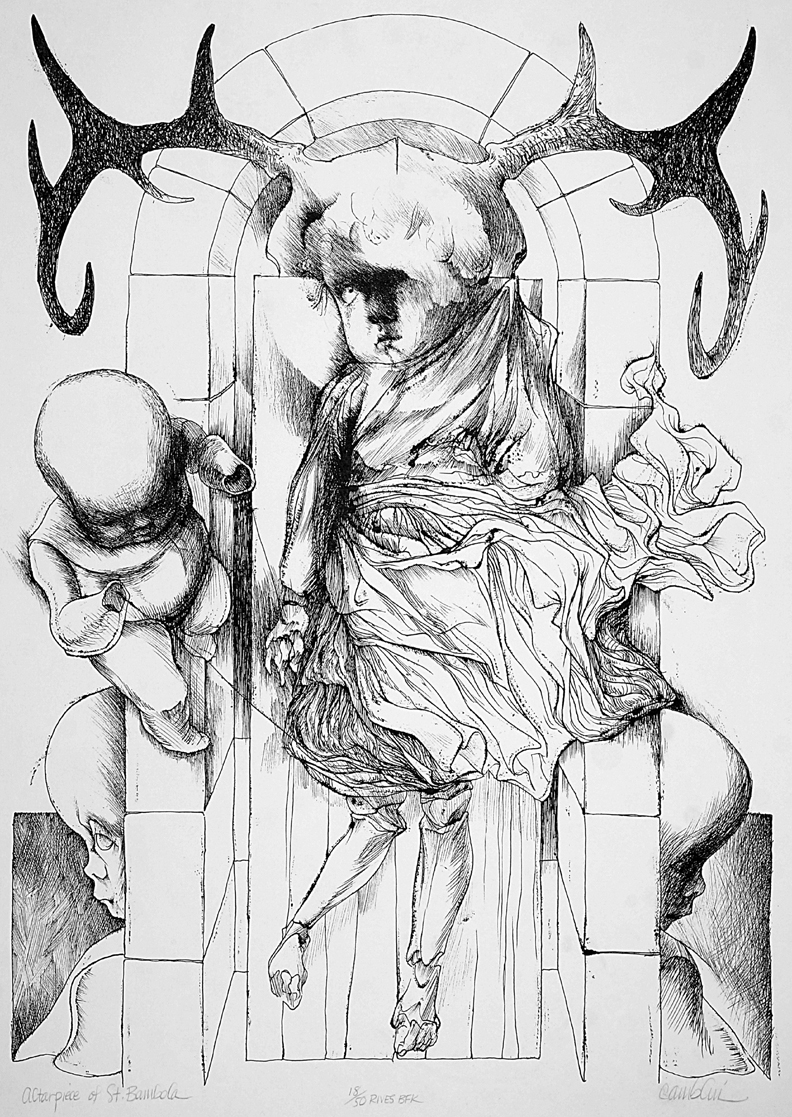

However, it was at the University of Utah that major changes sent him brooding on his future. Depressed by Salt Lake City’s philistine view of all but the staid and orthodox, he fled to the highest ground open to him – Rice University, in prosperous and art savvy Houston. Both contemporary galleries and collectors enthusiastically accepted him. On the St. Bambola series he was so proud of:

“St. Bambola died on my way to Houston, but her ghost still is haunting the process. The time machines and space ancestors are not removed enough yet. The recapitulation of high points in the work refers to the major changes and content and style of working and refers to none of the horrendous things and mental gymnastics that were involved in these years. And needless to say they aren’t in here now. I want to turn off my myth-making machine and escape the seductive powers of St. Bambola and extend the evolution that stopped with the Cicada series. Maybe it was finished with the song of the cicada.I wonder how to preserve the selfish me and still be aware of how ridiculous art is today, and yet a more cosmic side says, ‘you can’t change a thing.’ The Buddha came back to alleviate pain, so this summer my motto is: ‘Me First.’ Then perhaps I will come back into the world later and pay for its selfishness.”

The year he arrived in Texas, he committed to a busy exhibition schedule: “Bob Camblin,” at Rice University; “Bob Camblin: Recent Drawings,” at the Jones Museum in Oklahoma; “Beaumont Annual,” in Beaumont; “Dickinson State College Exhibition,” in North Dakota; Nelson Gallery of Art in Missouri; Norfolk Museum of Art in Virginia; “Seventeenth Southwest Print & Drawing Exhibition,” at the Dallas Museum of Art; and the “Seventeenth Southwest Print & Drawing Exhibition,” in Wisconsin, also included his work.

Camblin felt that galleries and museums didn’t curate exhibits properly because they made the same mistakes as the artist. Both usually expect more from the other than is possible. Without exhibits most artists would not financially survive, and without artists galleries and museums wouldn’t be necessary. Thus it is a relationship of mutual trust and commercial activity. Camblin had such a problem with “painting for money” that he often refused to take an offered payment. One patron had $100 bills sealed in a blown-glass tube so he wouldn’t have to physically touch it. And to be honest many artists and their egos are a fright for galleries to work with. Here Camblin explains to a gallerist how a show should work:

“We’re both familiar with the artist’s lifestyle, and so when we see a piece in an exhibit we comprehend the artist and all his moves. Even though the one-man show or retrospective is more explanatory, sometimes we get trapped in the chronological presentation of the latter. Also, in a group show there are too many tracks, and you really confuse what the art means. An artist should have the whole environment each time. No matter how small or large, nothing should compete or be compared. This will be done by the viewer, but the gallery or museum should help the artist by minimizing the interference. We’re still allowing the viewer to mistake the tracks for the animal. Divide that space. Overlap artists and give them a month to work. Even better, give them the month to work and then a month to show. Do you think it would work for the public? You will be allowing the public into the hallways of the process without showing only objects of process.”

Even as the ‘art game’ became more complex, he tried to keep his approach to it very simple – through faith and good work. He felt that things would stabilize around good work. If something happens and you lose face, your faith in your work will pull you through. Losing a good piece is just part of the cycle of the game. The game is a game of common sense and if you don’t understand the game, you should realize you’re not getting into it.

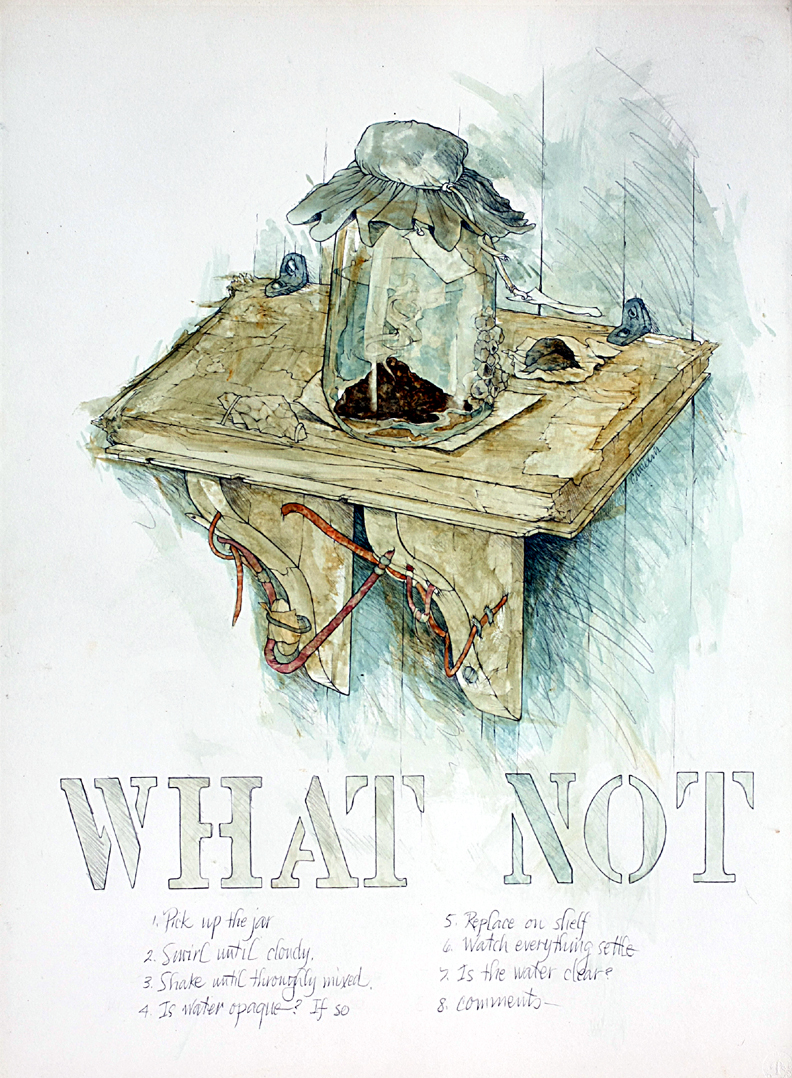

He remarked that his right hand has to know what his left hand is doing, and together they decided the path to follow. He felt that the muddy water had settled once again and his perverse logic had to unravel its game to reveal that the stumbling block was actually a stepping-stone. Paintings which feature jars of water represent this idea of turning a stumbling block into a stepping-stone. Let the water clear, see the path, unravel the game, and move up the step rather than stumbling.

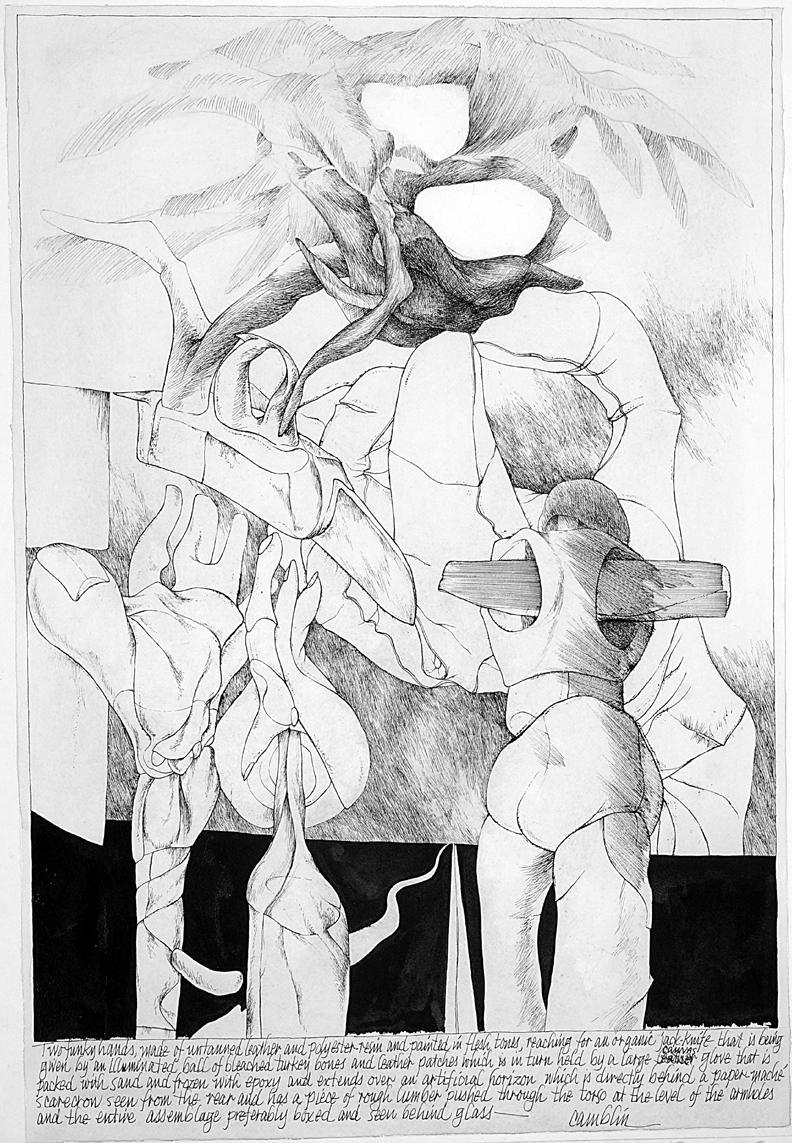

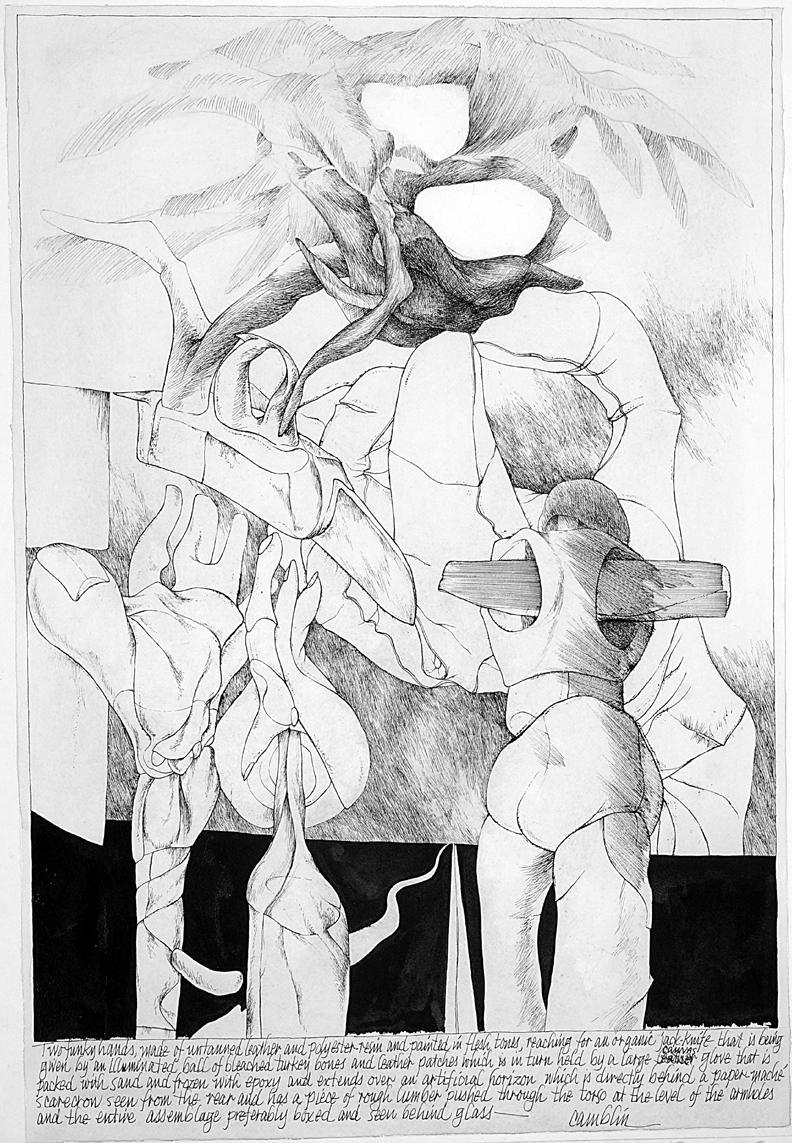

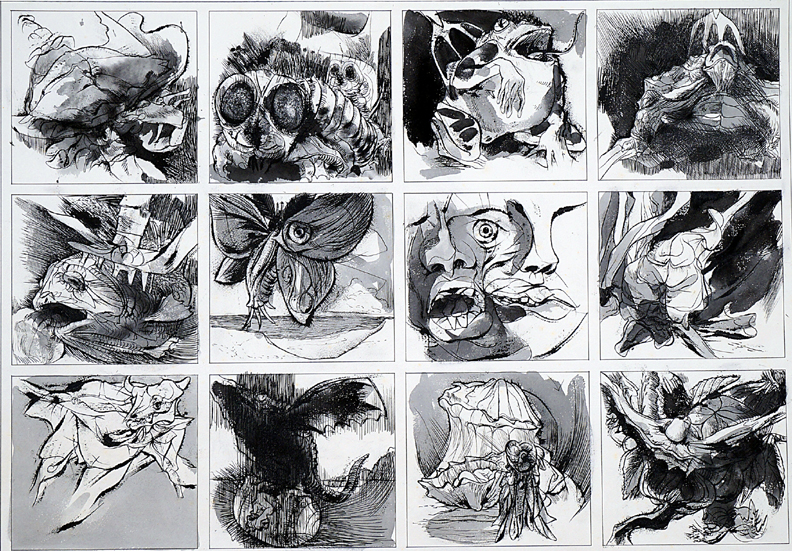

In 1967 he also started a series of scarecrows. He drew inspiration from Gunter Grass’ 1963 novel, Dog Years. Camblin’s scarecrows probably represented a loosely Germanic hastening of spring or renewal of life. As these scarecrow paintings progressed, the evolutionary themes expanded into another series of myths and legends, with elements of the lobster shell and puppets and especially the empty dried larva shell, further emphasizing metamorphosis.

In his later scarecrow drawings, he wrote descriptions of them as sculptures. It would seem the words describe exactly what the viewer sees. This, however, is not the case. Rather, the words become a disguise, hiding the drawing, as Camblin believed most words have always hidden the experience of the art (i.e., in The Painted Word by Tom Wolfe the author explains how Modern Art has become completely literary; that somehow what is said about art is more important than the art itself). In a Camblin drawing the blocks of copy are not solely put there to inform us, but perhaps they are inserted as a clue in the same way clues are discovered in a good Sherlock Holmes mystery. The text in his paintings may or may not relate to the drawing and may or may not be clues to its mystery. They are really, first of all, just shapes on the surface; shapes that should be enjoyed for what they mean to you and nothing more. Camblin would agree with Wolfe in that seeing should be believing:

“Painters and sculptors often reject words as dangerous to the perception of their art. Although being human, artists and critics like to talk their two cents worth and much of it is meaningless garbage. And yet, communication continues to grow, as well as the sophistry in explaining art. The end result would be that to see an image of the Sistine ceiling and discuss the aesthetic, social, and philosophical content of it would be deemed adequate enough to experience it in its own terms. This kind of experience creates a verbal awareness overlapping a century of wariness. Eventually it no longer becomes important to do more than recognize a potential for something to be art. The object disappears and the idea remains.”

His drawings of gloves, scarecrows, machined objects, metamorphosis, and St. Bambola are safely two dimensional, although there are elements of perspective when he suggests a landscape. These drawings are never defined by a light source, but rather, by movement with cross hatching across the two-dimensional surface of the paper. These movements and descriptions sometimes create a guide to proceed with the consumption of the drawing. He aims here to get you involved in exploring the artwork and how you could possibly discover something about yourself. Each of his works is a puzzle that wants to be solved. Some are easy, some more difficult.

The drawings also often include an extra data problem for the viewer. These data problems can trip you up. The problems contain two parts, one which is a simple code and a marvelous narrative device for understanding what the painting is saying and the other part is a simple trap – a dead end with no attached meaning. Camblin allows the viewer to focus on the traps, in hopes that they may discover something about the work or themselves as they move past the traps and discover deeper, hidden messages. Perhaps these drawings are his most reveled and he must have enjoyed practicing his own guerrilla warfare on a visually saturated, word-oriented culture.

There is nothing accidental in the drawings. They contain ambiguous windings that conceal as well as reveal and contradictory objects that always relate in some way intuitively to other drawings. They contain writings that someone will enjoy figuring out. There is something for everyone.

One thing to notice about his paintings is the strangeness that they represent, especially when the surprises and mysteries within them are often difficult to find. His paintings reflect an intention to question popular expectations of reality as much as – if not more than – the surrealist movement of the early 1920s. No longer satisfied with the structure of the existing world and the agony of the dullness of reality, he evokes the other-worldly and shares his desire to understand what these imaginative realities mean. His paintings do more than explore the relationship between the objective experience and dreams. They feature the elements of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur which require the viewer to step back and use their imagination to create associations with the reality of life. These actions unlock private, subconscious emotions, with the recalled event giving the painting shape and meaning.

The following artwork is available in the gallery: