“Now take a boy from the Midwest, from Ponca City Oklahoma, for instance. Teach him to speak Italian; then put him in an apartment that is 20 years older than his own country’s government. Put this apartment in the center of Rome about a block from where Julius Caesar was killed; where from his window he can see the church in which the first act of Tosca takes place. Let him become close friends with several Italian families. Let him visit the major museums and cities of Europe and live in Venice. Then bring him back and put him again in the Midwest…the results are these paintings.”

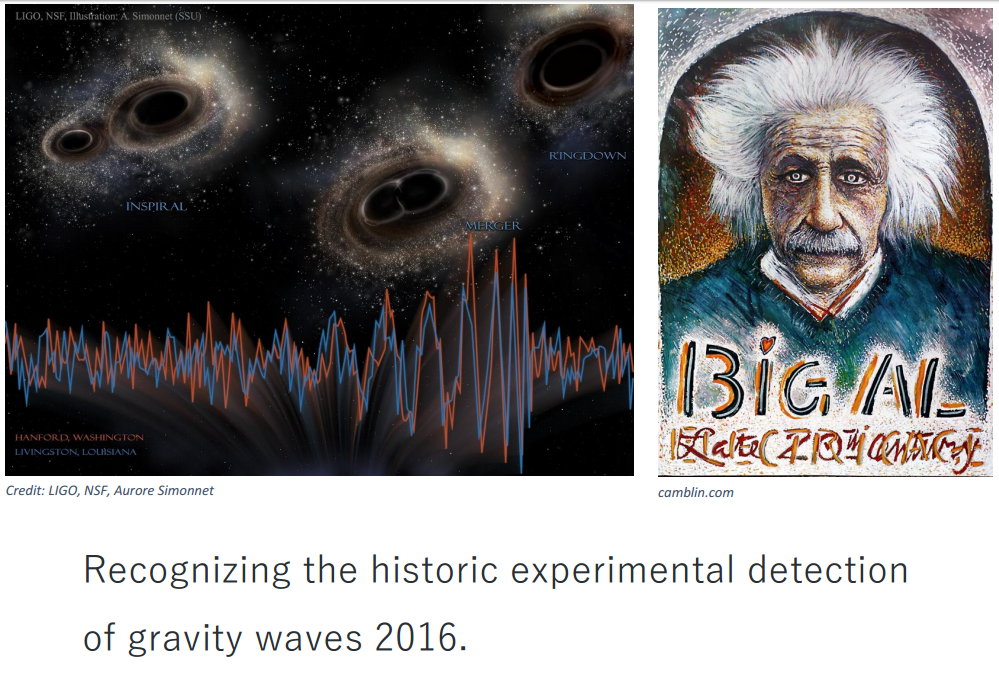

Camblin, quote from Time Magazine article, 1958

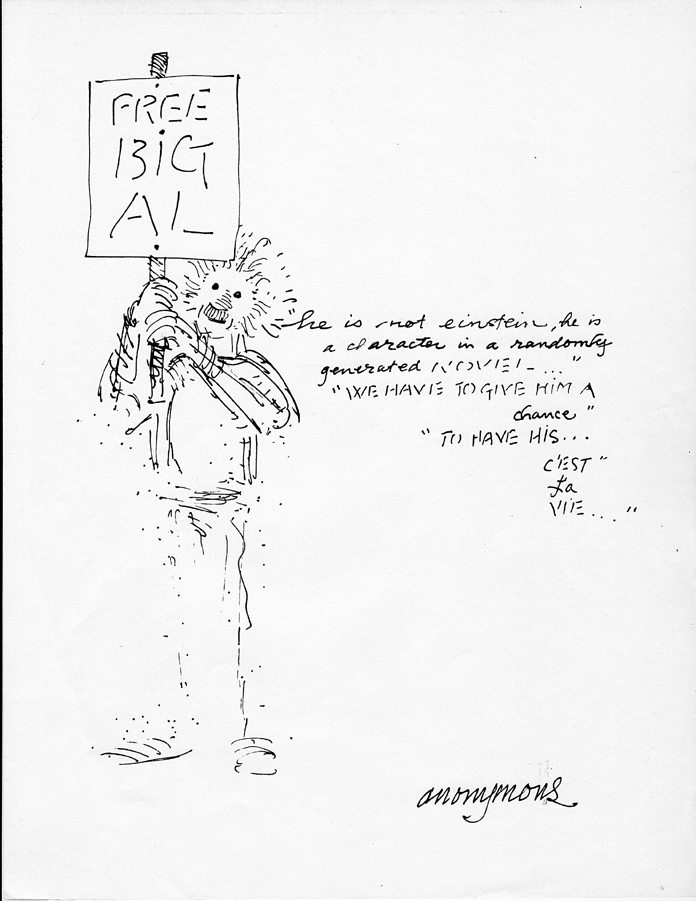

Anyone who has known Bob Camblin would have to agree that the above quote is undoubtedly the clearest, most logical, and convincing explanation of his artwork ever offered. He saw inspirational work and made inspirational work. When really pressed to explain his art, the most he would give away was that it took him 25 years to figure it out, so why should he make it easier for anyone else? Surely he said this in jest, but it speaks to a larger truth: he spent his life absorbing the world around him – its literature, its philosophy, and its imagery – in an effort to create artwork that connects in the most ingenious and curious ways. When asked what the meaning was, he would bellow:

“Qui sait! (French for “who knows”). There are optical pitfalls and traps which are devices used for ensnaring the viewers’ attention. These illusions are trap stratagems; delicate chromatic schemes which are used to achieve an end.They are about the transition or evolutionary period we are in, and perhaps one of the most tremendous because of the biological, chemical, and technological ramifications. We are spinning our beautiful silk cocoons after a period of 50,000 years of being a caterpillar. We proceed, but are unable to perceive the outcome of our new direction. Unity, convergence, cellular knowledge, and universal completion are but trapped within our small perceptive apparatus.”

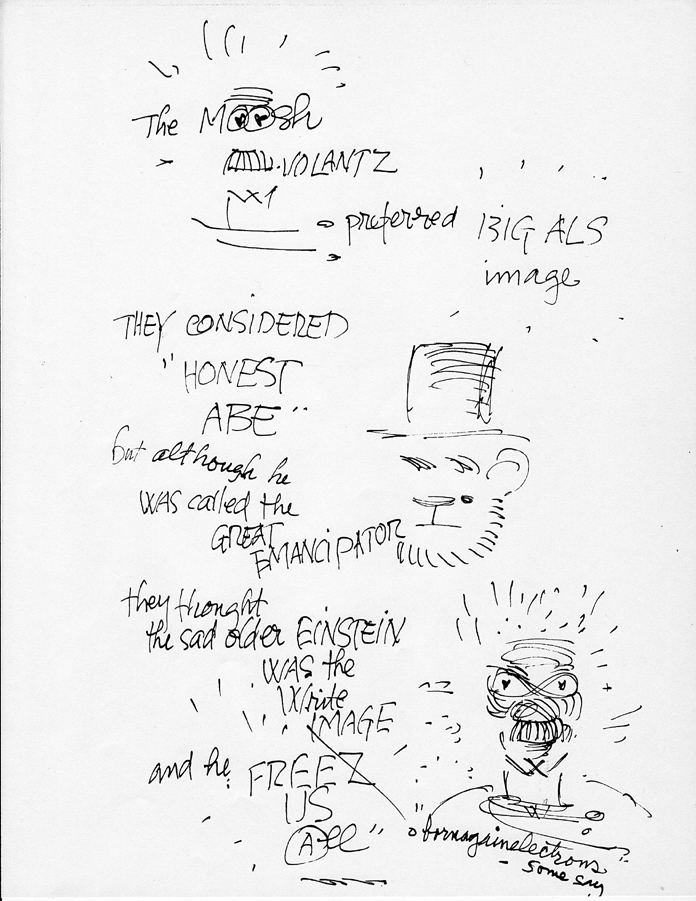

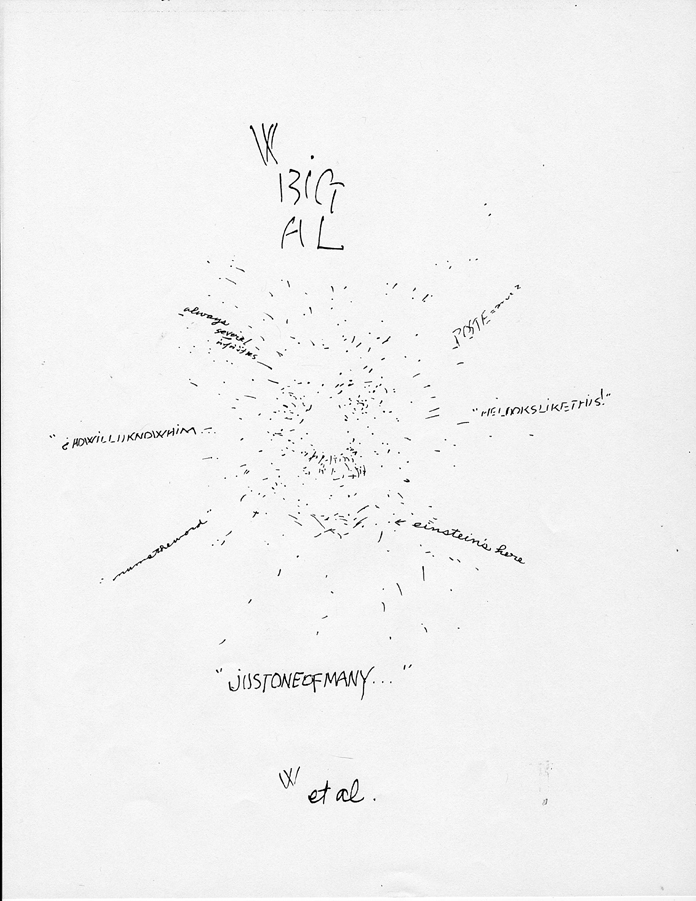

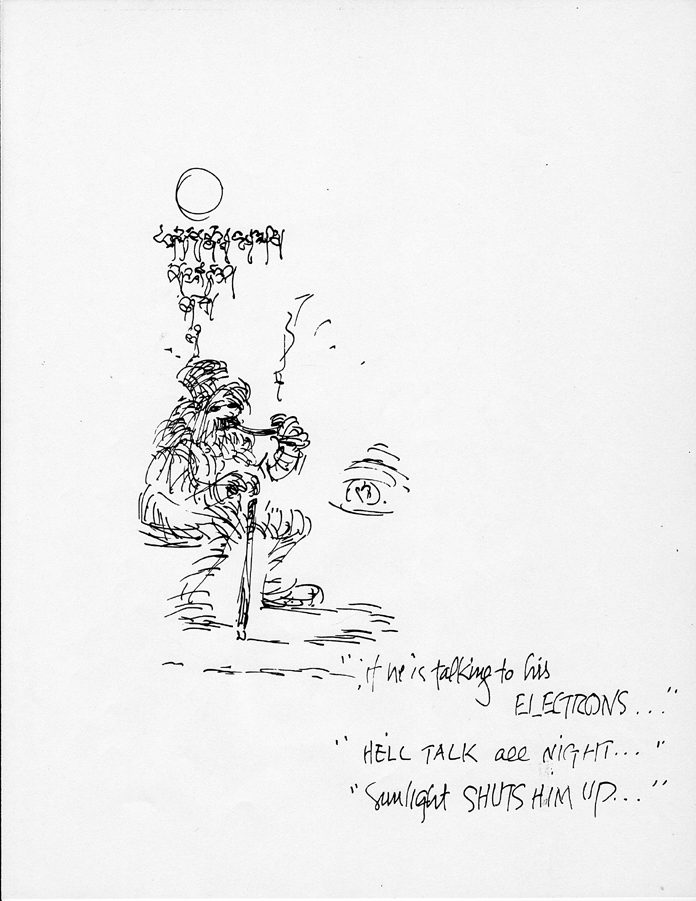

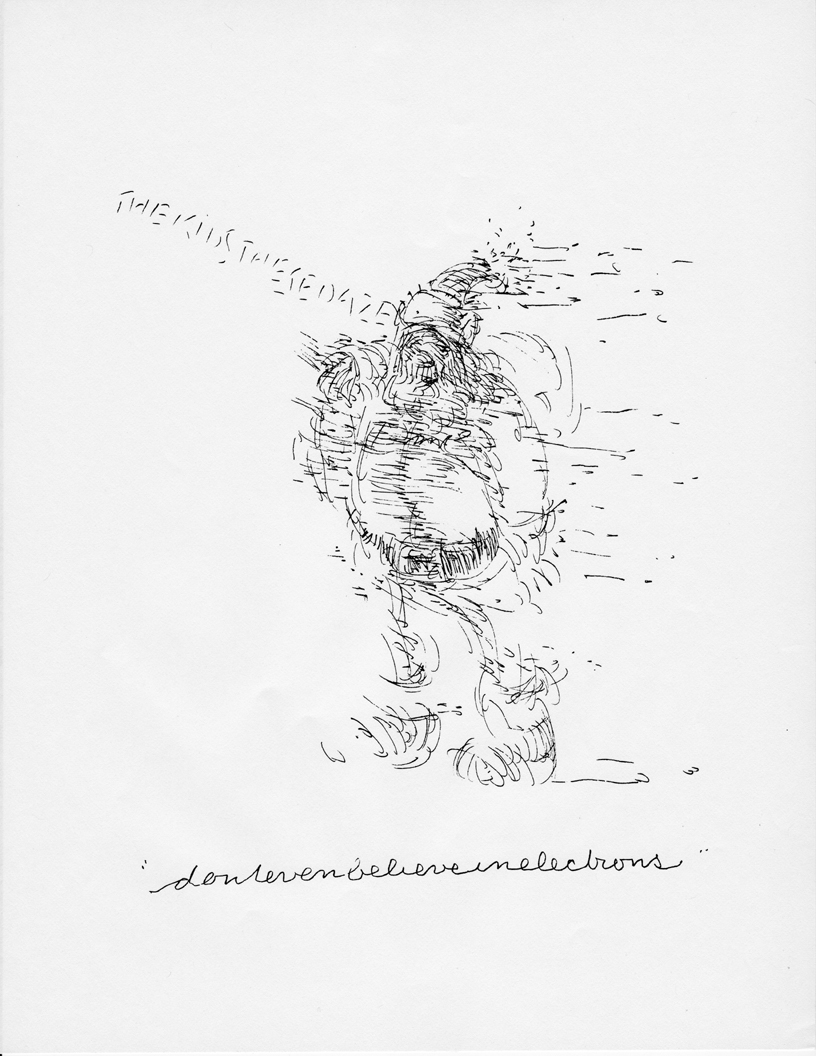

In fact, Visitors to his studio were often warned not to mention electrons – a favorite topic of his – for fear of starting an avalanche of monologues that could possibly last longer than the combined lives of all present:

“Some scientists think the descriptions of the atom are too complex. Then what is the simplest system to describe an atom? Why not follow the theory of thinking in other categories? What is 180° from accepted and then ask, ‘if this was possible, however wonky, why demand empirical proof before dreaming?’ Louis Pastor said, “Fortune favors the prepared mind.” Why not ‘more poetry in madness’ and assume the properly prepared mind will stumble upon the answer, or at least an unexpected direction. You can’t make dreamers out of statisticians unless they have always had the quality of visionary. The mechanics are the ones who will never understand because they know it all too well.When we’re not completely involved in drawing, or reading, or listening to music, we allow our more rational mind to say, ‘I am drawing, reading, or listening to music, but our natural-fit, flowing-mind covers many things. We are planning the hunch, the inspiration, the solution, and, behold! It seems to magically appear.”

The professor in him is always teaching; teaching us to rethink learning and how to fail, teaching us to learn to relax, teaching us to learn to feel, and teaching us how to really think. He firmly believed that you couldn’t just look at art. You have to be in it, doing it, living it. Everything is art and to survive is to become an artist. Camblin would encourage everyone to explore their art, to become artists, “And not just a fine artist. Any kind will do! And you don’t have to be good at it!” He stressed that we’re all creative, but we lose our magic by understanding everything instead of knowing. Understanding is the ability to comprehend something. Knowing is the awareness of knowledge to a select few. To have a secret is to know something someone else does not. Remember the old saying, “I thought I knew but now I know.” You may understand meditation, but you won’t know it until you practice it. Likewise to be an artist is to sit and listen, to discover the good vibration, to search for the way through truth; that is art of knowing.

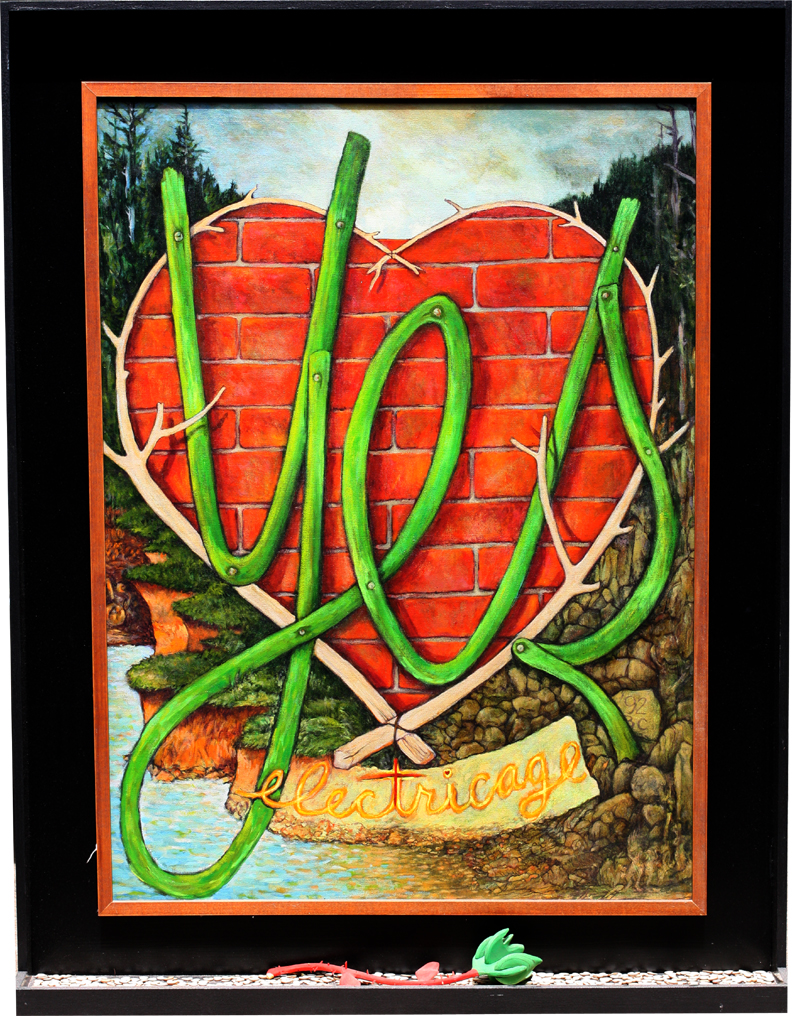

His artwork tries to communicate this line of reasoning to the viewer. The viewer perceives the story and it is the viewer’s imagination that determines how their story unfolds. This is true of any painting. But there is an undeniable difference in his paintings as they often contain multiple narratives and the stories are purposely ambiguous. He often spoke about the hidden realities crafted within his paintings:

“I hope I don’t get literary and precious about this since I obviously wish I was a writer. Someday I must really ask myself why I write blank verse on my drawings.“Come on Camblin, it made you burn all the poems you wrote in the service and in Kansas City in 1954.” Somewhere I must put in a few notes on my use of haiku, and the subsequent development of perception as a self-revealing, self-proving device for artists. My god; that does sound pompous! Still, it is the device or method I haven’t been able to teach in a class, unless the student is ready. It sounds a bit unreal, and probably for this generation, acid is easier.”

His use of haiku forces the viewer to focus beyond normal perception by opening up to peripheral stimuli. He describes the experience: The illusion is examined and logic is applied focusing us on the painting’s environment, the process crystallizes the experience and expands the moment of feeling. It allows you to experience various sensuous stimuli at a later date by recalling relatively unimportant aspects of the experience. The structure can allow philosophic overtones to a momentarily intuitive response.

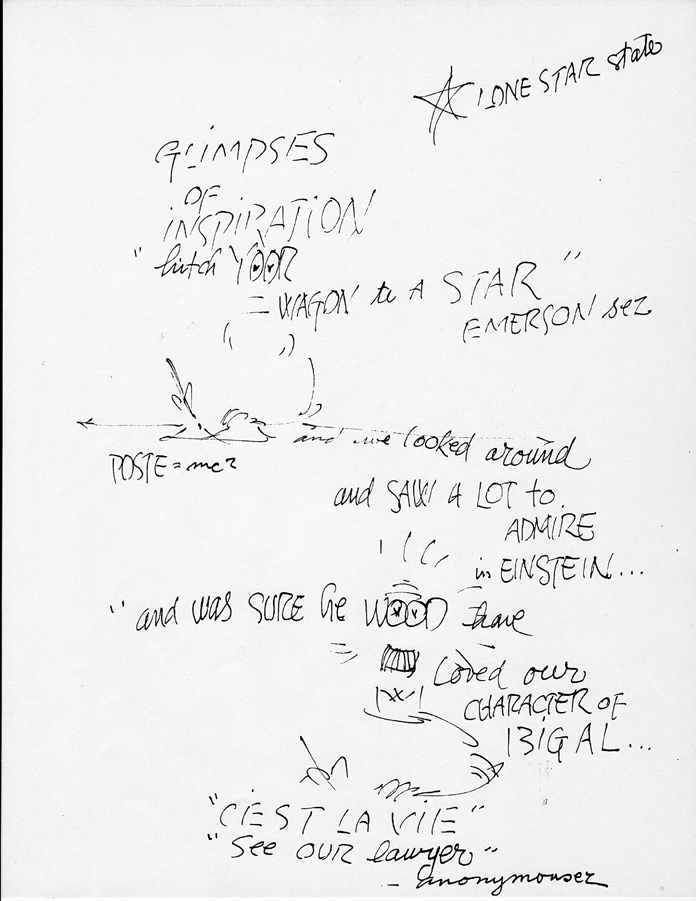

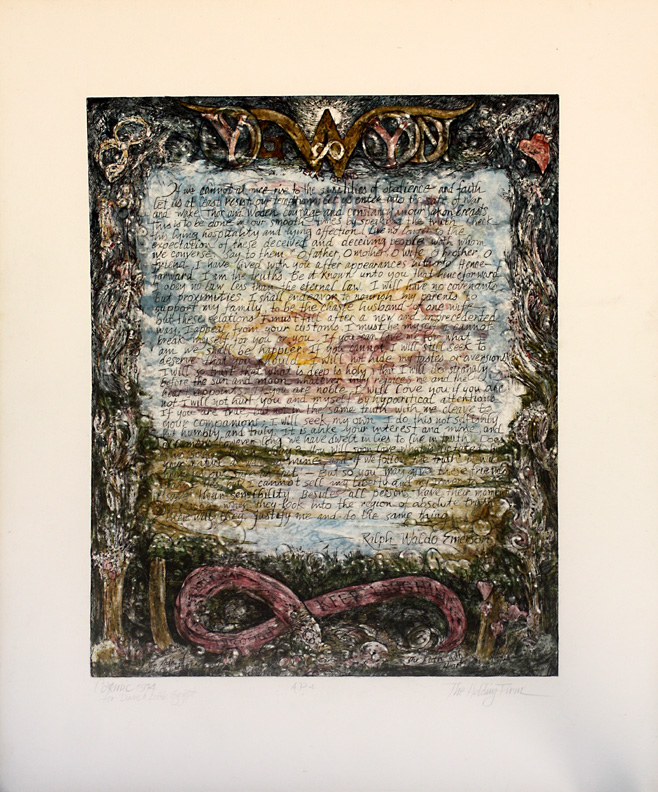

We do not know exactly what moved him toward painting, but we do know he was influenced by reading Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, and Lao-tzu. He also had a craving to impart direct, personal, and unmediated experiences into his artwork. A writer at heart, he found his original relation to the universe was through painting. He believed that literature and art were not separate cultures but rather intertwined in a seamless whole that included science and religion. In his journal he wrote, “Some say Picasso said paintings are not to decorate the walls of a room or apartment, but are instruments of war against brutality and darkness.” Ralph Waldo Emerson’s writings are timeless because of his love of nature and his insistence on every individual’s worth were his literary instruments of war against brutality and darkness. Camblin sought to unite art, literature, and philosophy in his battle with brutality and darkness too. He chose the only weapon he had training in – the paintbrush.

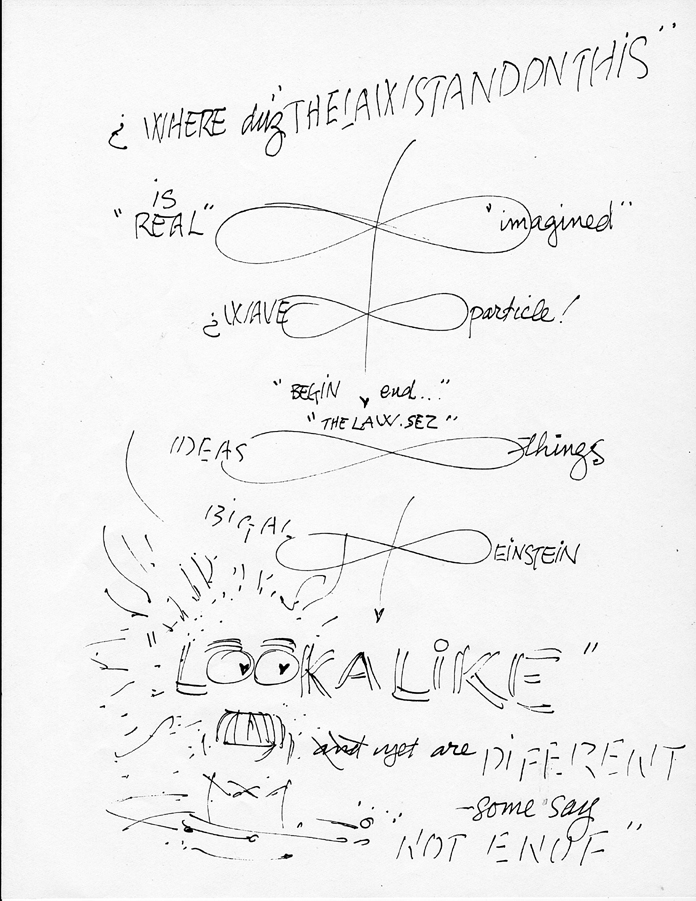

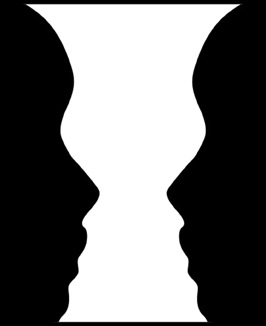

Marshall McLuhan (noted philosopher of communication theory and public intellectual) said, “Language extends and amplifies man but it also divides his faculties. His collective consciousness or intuitive awareness is diminished by this technical extension of consciousness that is speech.” Camblin believed that to complete this paradox, this same language in a haiku experience focuses the mind into a collective moment and instead of dividing, allows the unification of all senses. This whole concept of narrative devices, associations, collective moments, and the unification of senses described by McLuhan and captured by Camblin’s paintings, can be clarified for the reader with a few good examples. Let’s start with the famous drawing in which the viewer sees a vase or the outline of faces (Edgar Rubin’s “Vase” 1915). There is another ambiguous figure/ground illusion of a witch and a young girl (W.E. Hill’s “The Hag”). In the drawing of the vase, the brain eventually sees both the vase and the faces, but not at the same time.

How did your brain decide if it saw faces or a vase first? Scientifically, this decision is based on many cues: size, shape, color, and edges. Camblin took extreme advantage of the figure-ground organization and perceptual grouping as a means to an end. Size, shape, color, and edges were all used to provide the viewer with a feeling of surprise along with an emotional uplift – the same feeling you get when you are seeing a vase and then you finally see the faces. The “Ah-Ha, I see it now!” moment; this is knowing rather than understanding.

His paintings encourage you to open a circuit of perception. Empirically, they demonstrate that we’re always making traps and living precariously within them. The reason that the Zen monk laughs, or the reason we laugh when we solve a puzzle like the vase puzzle, is because of the euphoria of discovery. Scientist’s call it the “Eureka!” moment. It’s the moment of knowing something with the whole body and soul rather than just understanding with the mind.

Whirling in tighter and tighter circles, Camblin goes on in his attempt to explain his paintings’ eureka moments:

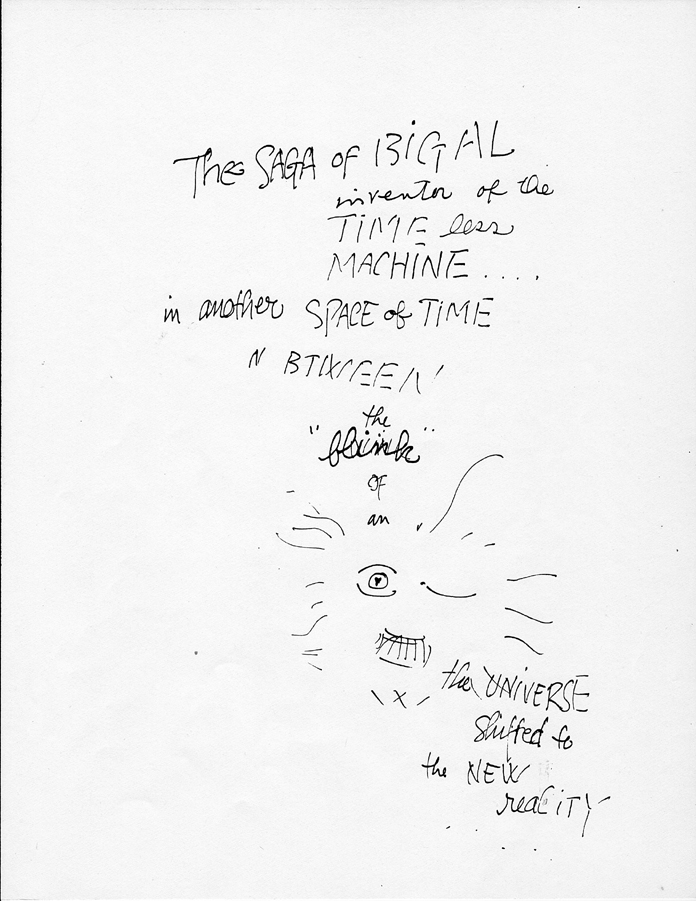

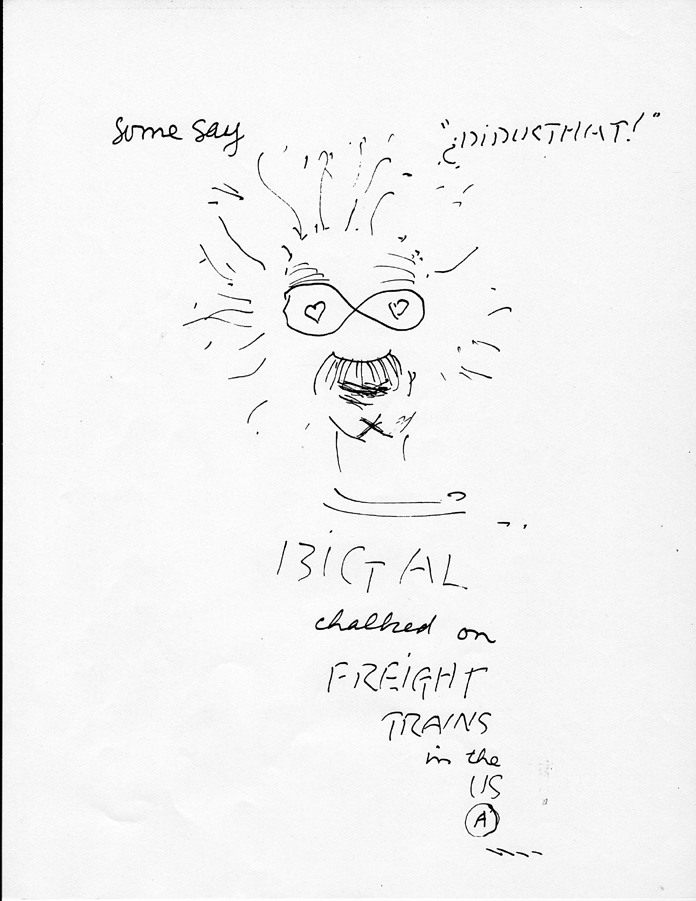

“In an infinite universe of time, all probabilities will occur. Everything we can conceive can or will occur someday. We can never comprehend anything as simple or complete as this. We find truth through paradox; the gateway for a moment of either/or. It’s the edge of things, the flicker, the moment in both concepts; the flash of insight in a pun, a paradox, a mystery, a joke, hyperbole, and anything and everything is caught flowing. But to hold onto disorder is impossible. Our chemical / electrical computer brain all but requires order. It is into logic and the rational. Just think about what we perceive; marvel at the scale and awesomeness and realize it’s just a dream of sorts. That it’s overwhelming when you look at a drawing is because it relates to how many types of order you can find and what your perception is showing you.”

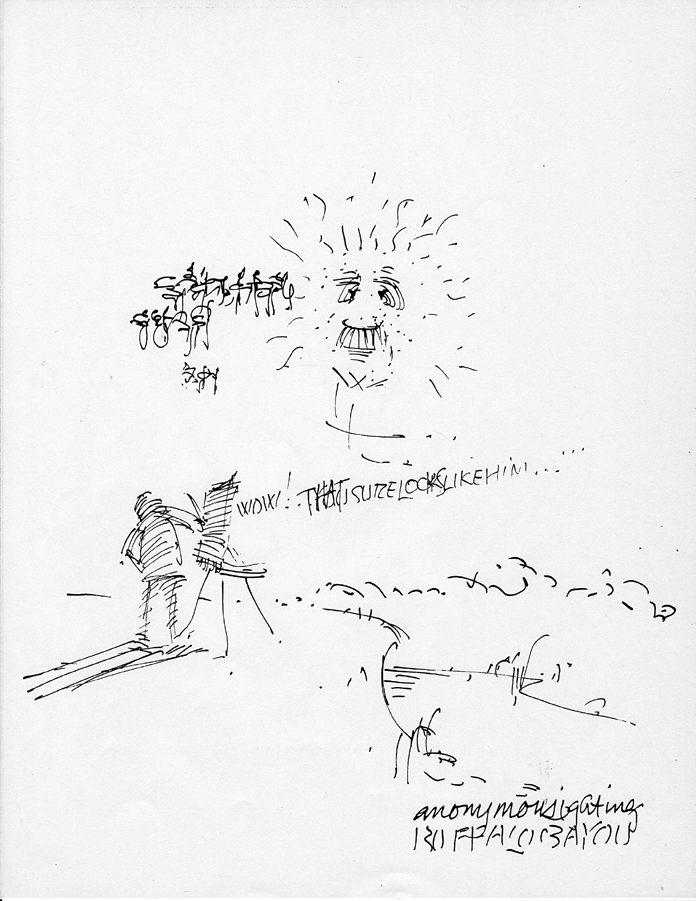

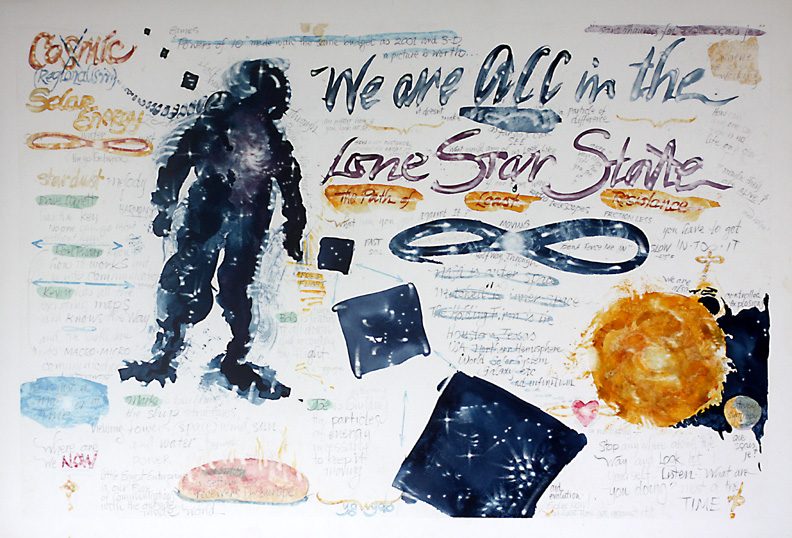

This next example is one you are sure to get. In this sketch of a waterway lined with trees, a figure-ground organization uses size, object shapes, color, and edges to its obvious effect. Can you find the figure? How many more narratives did you find while looking for this one? When you look at this sketch, remember that art is the ordering process made visible. Art makes the order visible for a moment. Drawings and symbols and images are the tuning-forks of the unconscious. It all relates to you and how many types of order you can find and what your perceptions are telling you. (If you don’t see what appears to be a female figure, notice the eyes, nose, and mouth on the left side of the tree).

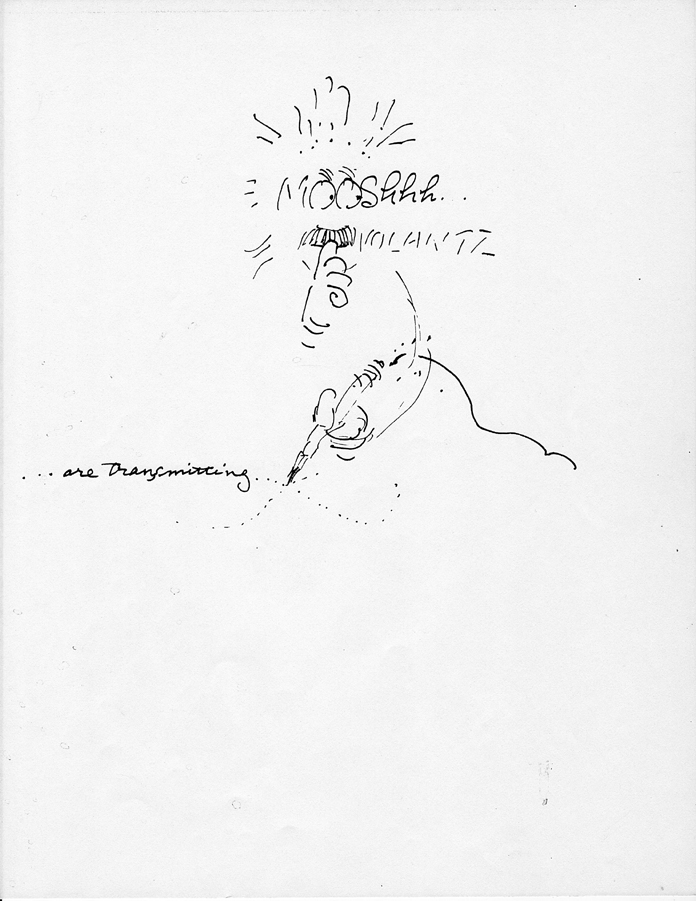

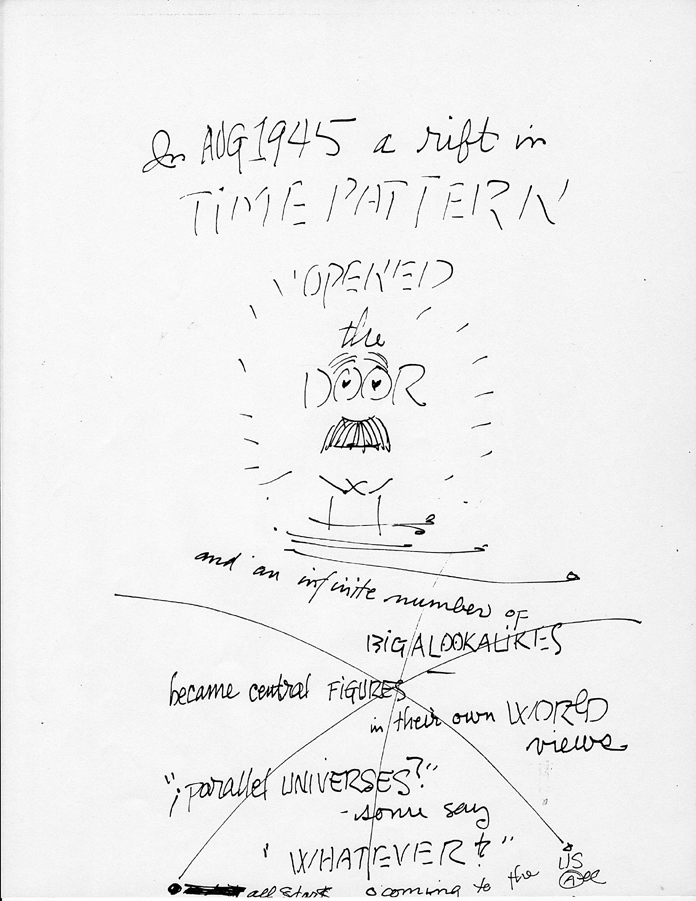

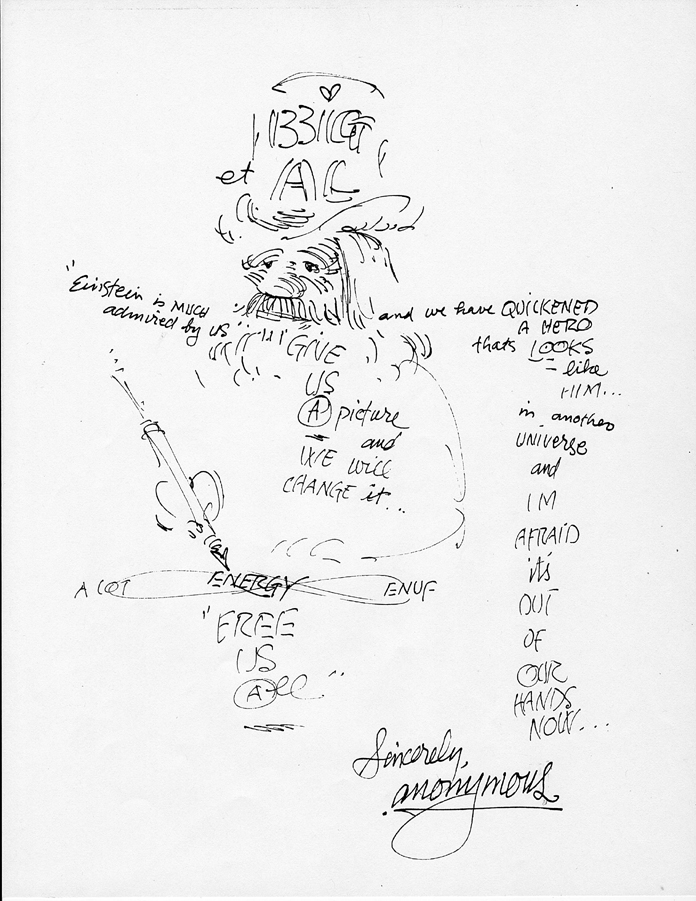

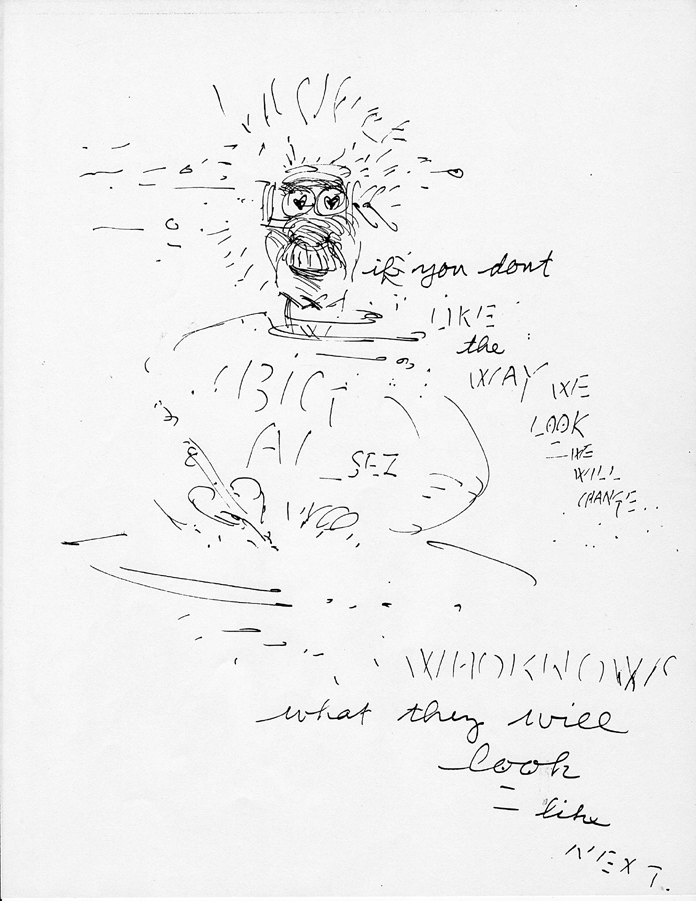

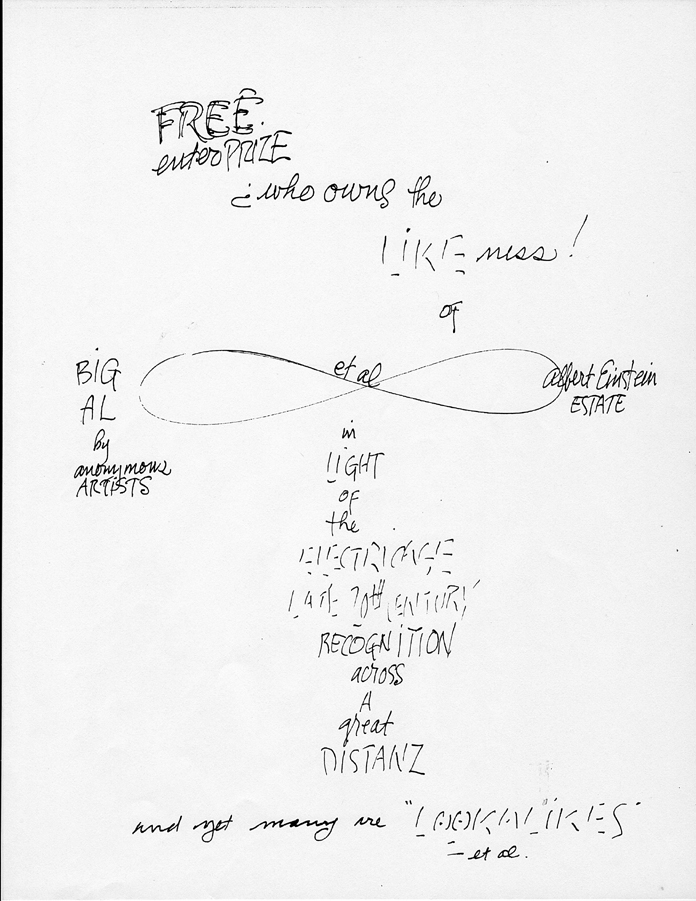

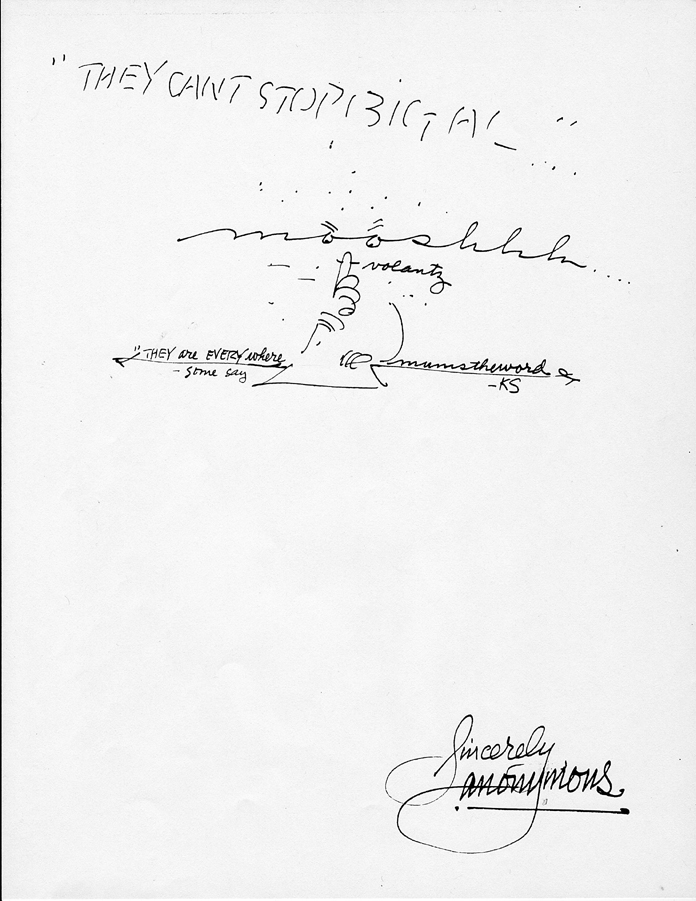

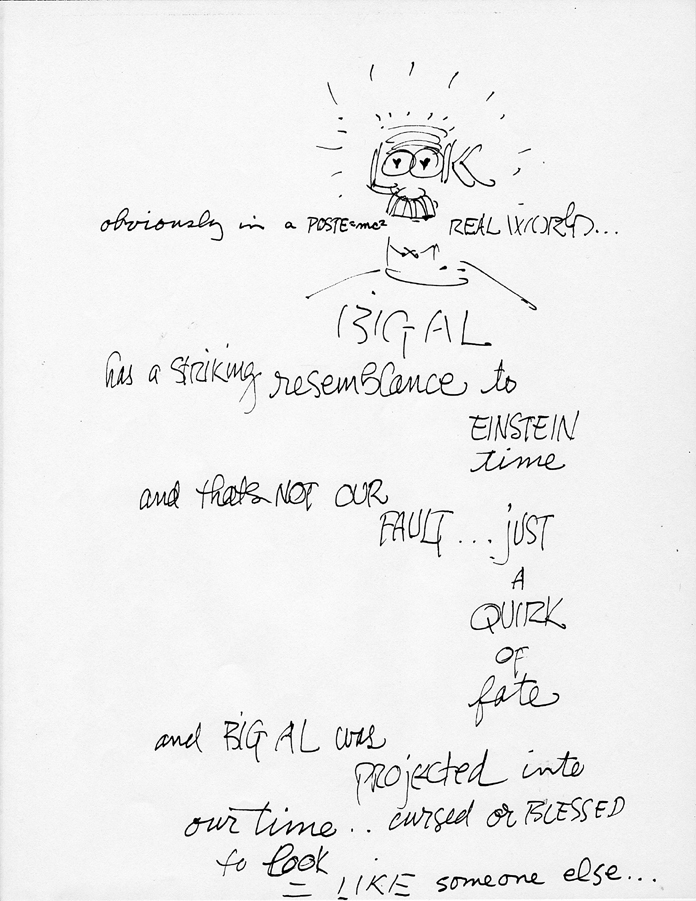

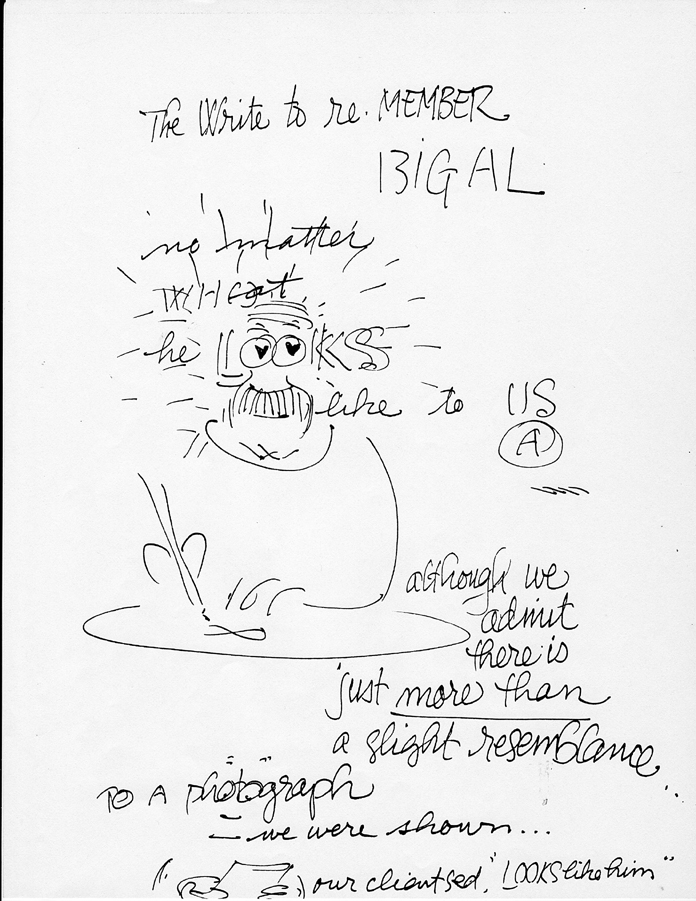

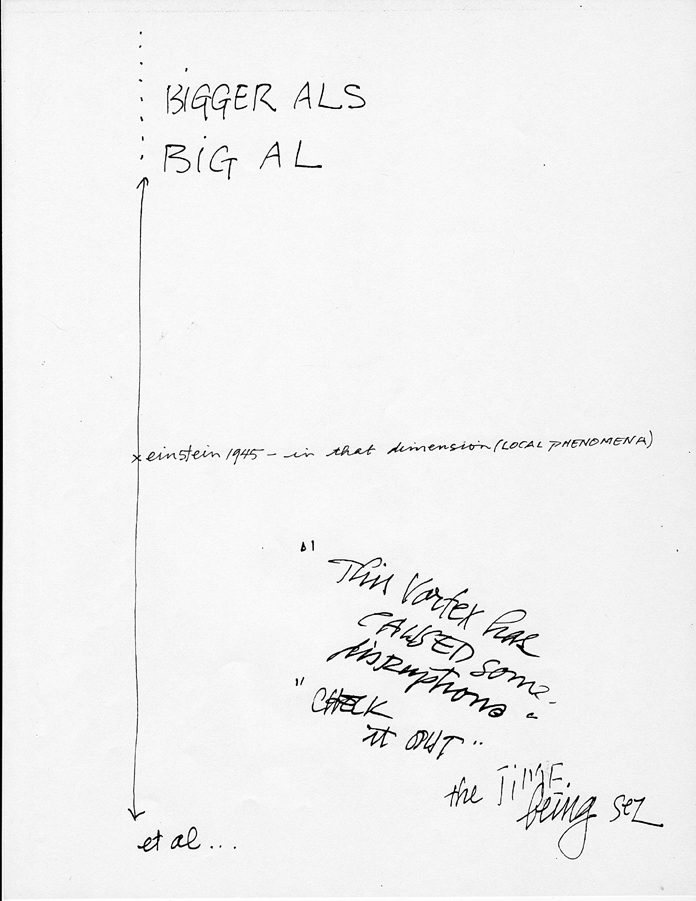

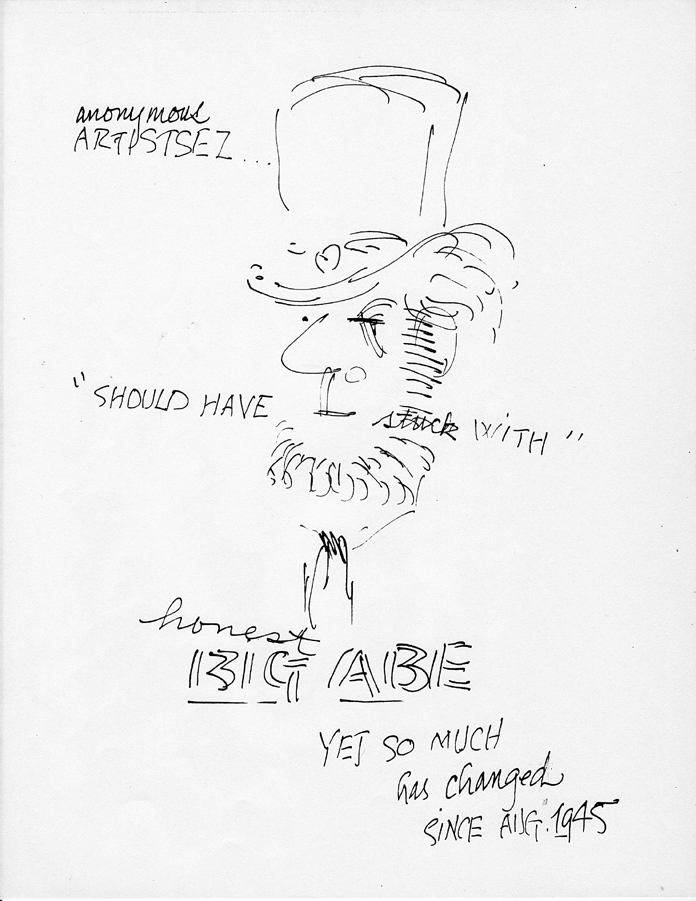

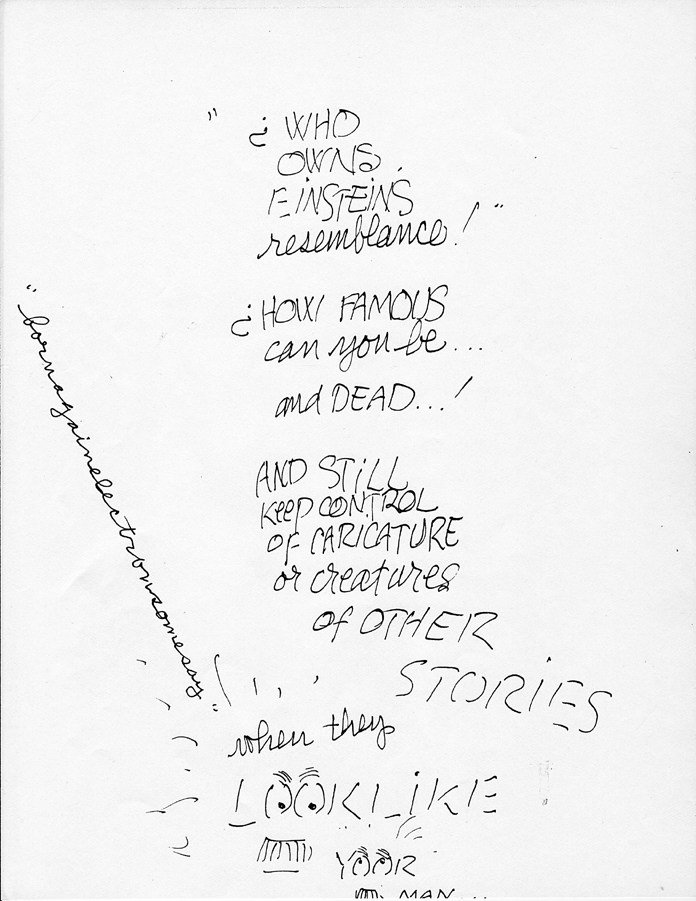

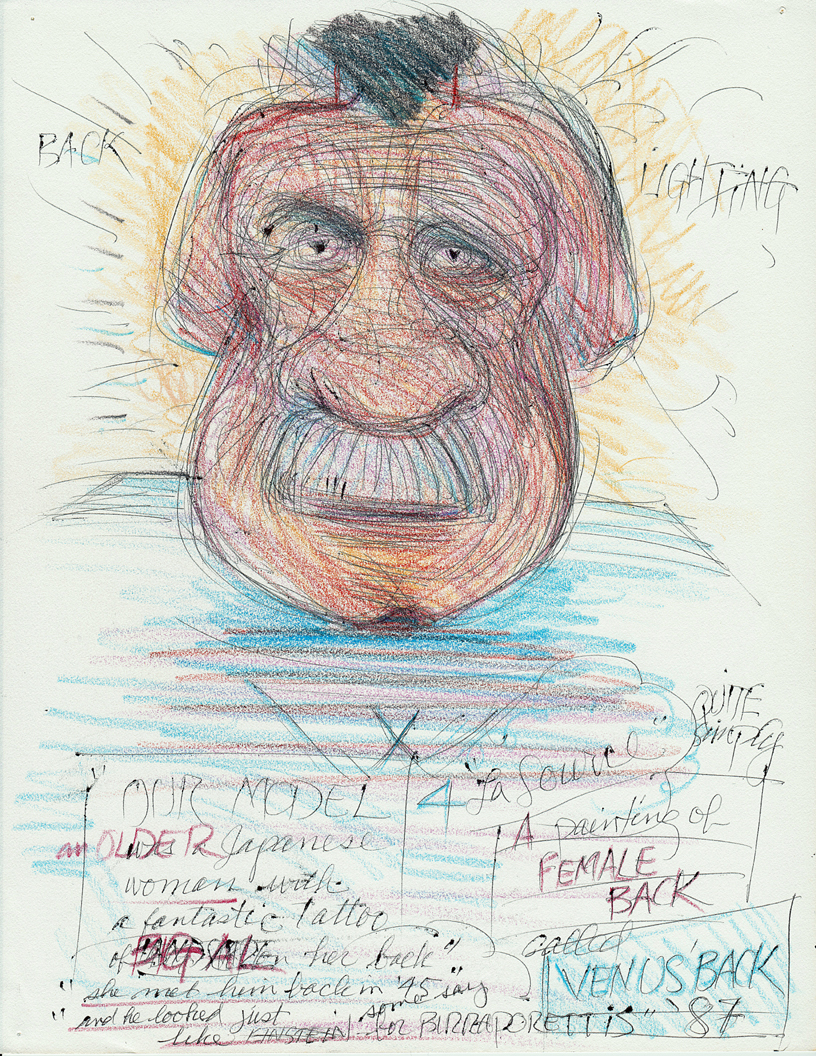

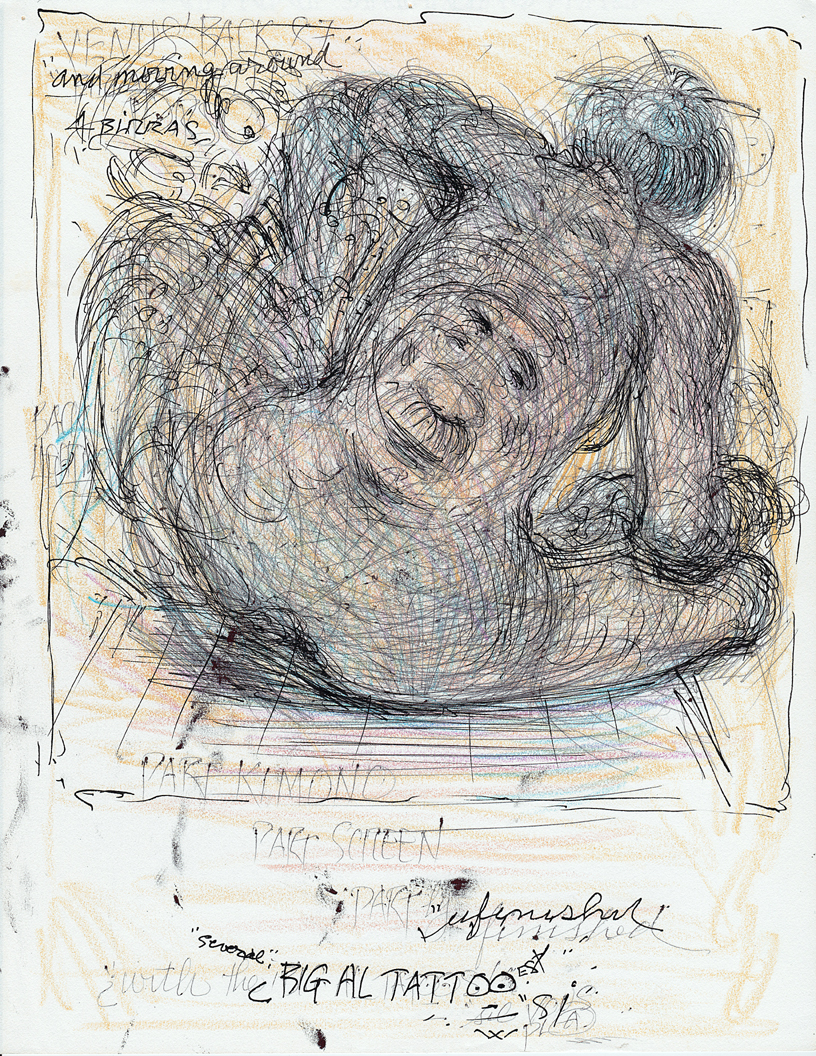

Notice the artist’s notes across the bottom. These “DRAWritings,” a term coined by Camblin, muse about curious events in the artist’s life; strange occurrences about electrons (don’t get him started, we’ve been warned!), visual impressions of the world, and the banal and incredible relation between art, life, and the “hall of mirrors” game with which we are all inexplicably entwined.

Our last ground/figure image is more difficult. This drawing style purposely challenges the boundaries of perception. As with Rubin’s “Vase”, one usually sees the figure or the background. Do you see the parrots? The artist wants you to see the parrots first, so that is what you will see. Or you may be one of the lucky few that see the mustached individual peering from behind a veil. If you are having trouble seeing the eyes, nose and mouth of the hooded man, don’t give up. Try standing 10 feet back from the image or squinting.

The ones who see the parrot take in an impression of a parrot situated with its two chicks and quickly move on. Others, however, do not accept the parrot and instead see the veiled individual. They try to create meaning out of brushstroke stimuli, their minds subconsciously racing through hundreds of calculations a second in an effort to weave a jigsaw-puzzle explanation based on each one’s unique historical-optical experiences.

Gestalt undoubtedly factors in these paintings. This school of psychology concerns itself with the modern study of perception that in part, emphasizes that the whole of anything is greater than its parts. Camblin’s paintings provide a fertile ground for discovery; whether they are psychologically induced, or a product of a fervent imagination, or due to influence and suggestion, or merely the written word taken as the key – it is up to the viewer to decode and decide. Are you seeing these symbolisms as Camblin thought you should or are you just imagining that you are seeing them? He would never tell.

To borrow the art-speak used at the time: their minds were being blown away. Their perceptive circuits are opening up to alternative options of what this drawing’s reality might be. They are “seeing” without looking; akin to how a Zen monk sees without looking. The monk “sees” that which does not exist. The viewer might be seeing that which does not exist, but for their own unique neural pathways. They have performed the miracle of transforming collaborative dots and dashes of water, pigment, and opaque white into a meaningful experience that goes beyond what the artist intended. That is creativity. That is what we all have and sometimes it takes art to remind us of it.

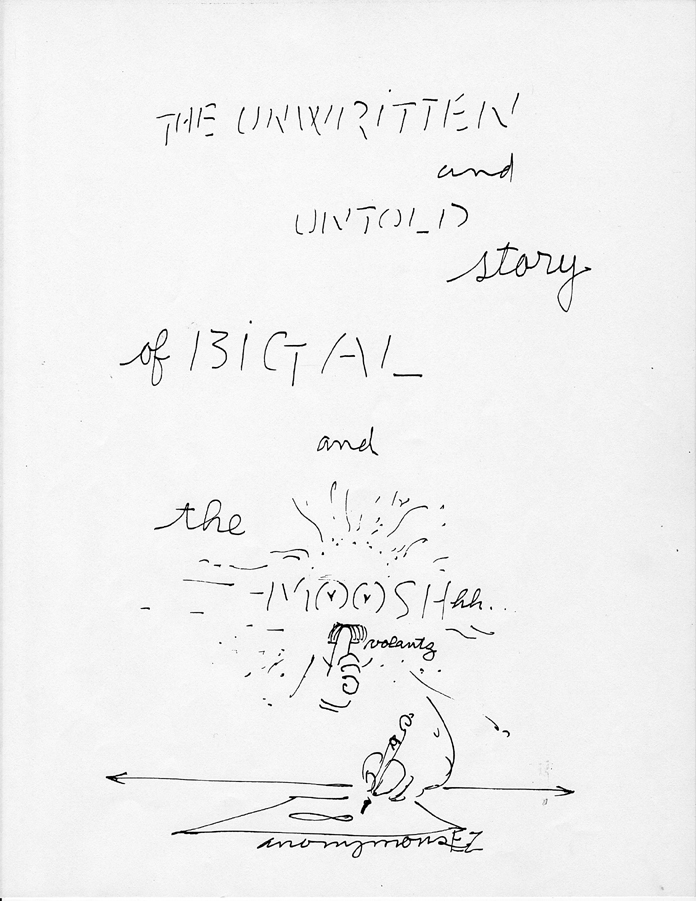

Quite often, visitors to the artist’s studio were treated to out-of-this-world stories that seemed to come straight from Alice in Wonderland. In reality, it was just the creative genius deep within the myth of the current drawing, suddenly drawn back to the “real world” to provide us with a complex yet revealing narrative straight from the mind of the artist himself:

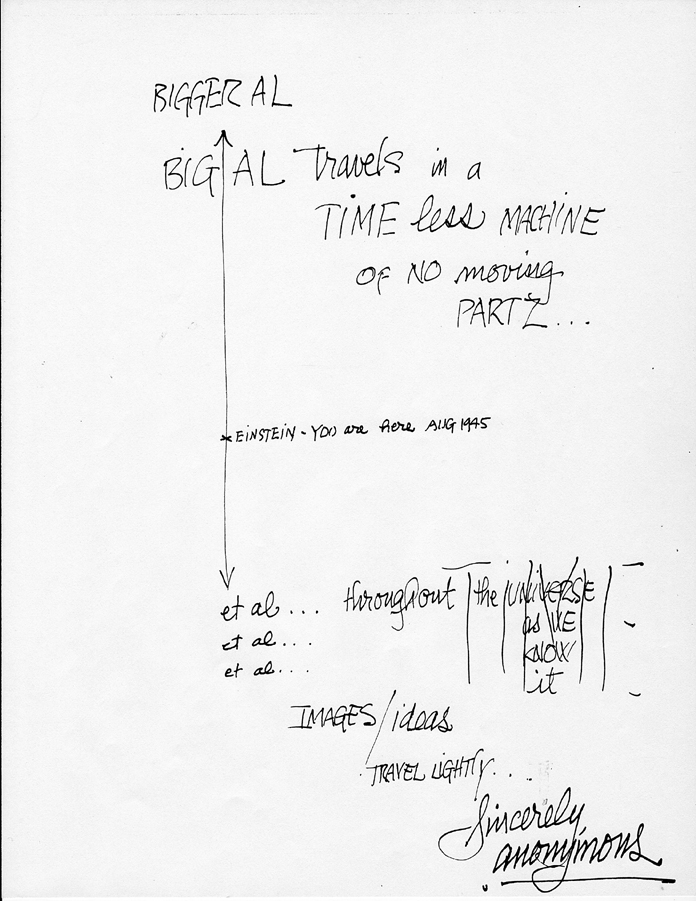

“Being overly concerned with extra-sensory perception defeats the understanding. It is good that others are making headway, but focusing on telepathy is missing the point. Rather it hits a point, but misses the system. Telepathy exists in all people. It can set you free, as long as you think about it as a power to learn about one’s self and not as a power to manipulate others. Let me explain. Our brain lives in the future and our body in the now. We send out probes constantly. The barrage of data, on the order of hundreds of points per second on our senses, reduces the distance they can travel in seeking alternative futures. Our mind goes into the future by microseconds of real time and picks a pathway to an alternate future and returns it to our body.

“The more we can diminish our wants, the more the mind can move along tracks of the future, selecting for each moment its direction. Under normal conditions much of the future is mechanical, but in stress conditions it is more focused, and the probes go farther and farther ahead in time to select the proper moves, just as in chess. The Buddha says… that wants can focus us away from the path with heart, and the simplest way to open up to ‘the way’ is to do as he does – desire nothing. Doing this, the probes open up entirely. Yet as humans we fall short. We desire food and need air to survive. And even these are within the path of least resistance. We in essence go into the future always in varying depths. Then our body muscle follows what the mind has selected. This duality is nicely handled by the wave and particle paradox of the electron. In the human, the mind is the wave and the body is the particle.

“The selection of objects as phenomena; the group of objects as phenomena; the transformation as phenomena; the free association as phenomenon; and yet the drawing is the focus. The hands by which the phenomenon is experienced changes the object as with glasses of red, yellow, and blue filters. Each person reacts to the object in a different way – some verbal, some visual, some tactile. Since anything can turn into phenomenon, have you focused and stopped seeing? With phenomena, try looking again and again, this time with humor.”

By this ingenuous juxtaposition of appearance and reality, Camblin brings such intensity to his art that it becomes part of the viewer’s human existence. The viewer is decoding the collection of pigments left by someone experiencing the mysterious and unaccountable events of life: the processes and products, the random and found images, and ideas and emotions:

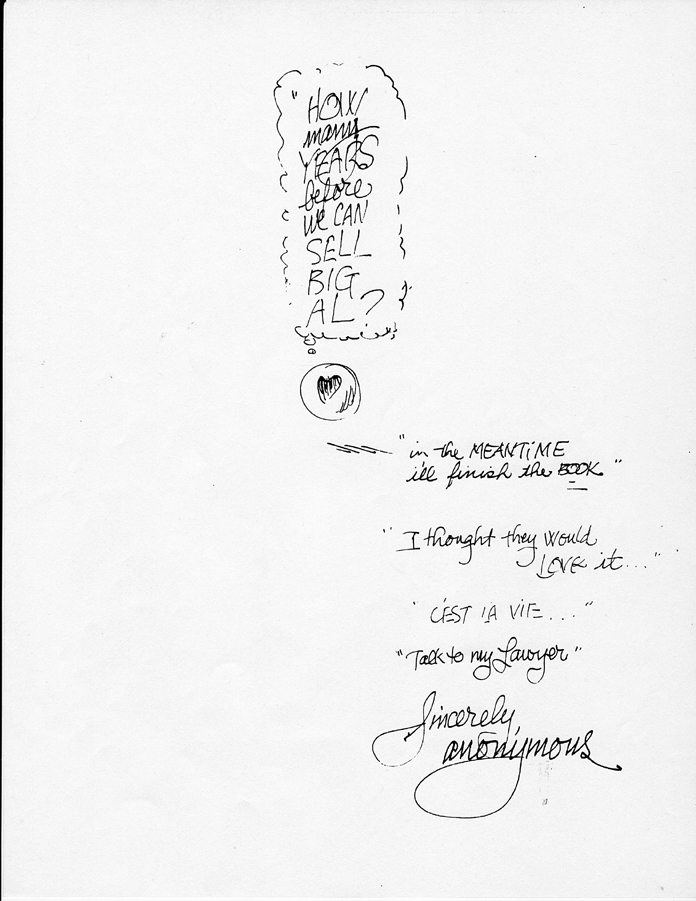

I still use the image-finding technique, but I’d never settle for a few clichéd grotesque figures. In every series I reject hundreds of simple ideas a quick wash and some jazzy pen work would bring off. Maybe I wish I could do it, but I was hung up on Vespignani long enough and I know that it doesn’t take much to make a selling gimmick. I may be poor, but I’m pure. I wish I could be a little more deceitful.

His art is only limited by the integrity of the viewer’s imagination. And that is his point:

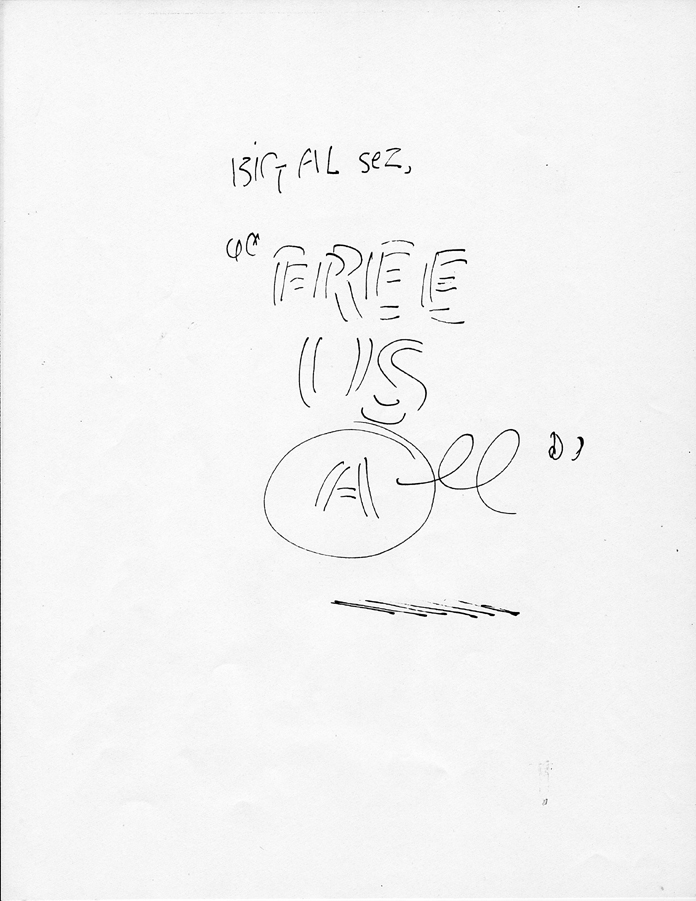

“Don’t be limited! Embrace both the profound and perverse. Strive to understand the mysterious. Remember to laugh. That is the whole point!”